Georges Simenon

Georges Simenon

LICQUORICE ALLSORT

Let’s assume (in a considerable stretch of imagination) I’m a professional footballer - though retaining my same characteristics and personality. A team bollocking from Brian Clough or Alex Ferguson – yelling, telling you stuff you should know anyway – would be the last thing to get me motivated. I wouldn’t be interested in the team, in any case, apart from their physical attributes. I’m not interested (much) in fame and glory. I would, however, be interested in scoring unusual and perfect goals. I can/do accuse myself of many things but I’ve no interest in money, apart from having enough to keep me going. But it’s my not being a team player interests me. How pop groups stick together more than two weeks bewilders me. Well, the desire to accumulate of oodles of cash no doubt, helps inhibit a break up. And groups of lads – particularly lads – walking round smiling in sync, laughing (inordinately) at one another’s jokes, fill me with something like fond pity. I’m not even very keen on communal displays of grief: ‘coming together’ of the Spirit of Liverpool – or Manchester – variety. And yet, of course, I feel the occasional pull and tug. The film ‘Angel Voices’, written over thirty years ago, shows a boy separating himself from the group – and his regrets.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately of the implications of solitude. The great heat of the last week or so has caused comparisons, first with the summer of 1995, and then – as it got even hotter – with 1976. Both years, I realise, were milestones for me and in both cases retreats from the world. In 1976 I gave up teaching for writing – the pretty cheerful life of the classroom for the study. One of the first jobs I had done with the little house I owned in South Yorkshire was to have a study area made with book shelves, an extension of the living room – the place wasn’t big enough for a separate study. I have a local press photograph of me against a backdrop of books at my Olivetti typewriter, working at a table I still use when writing. Though insecure, ’76 was one of the happiest years of my life. I’d loved teaching but wanted (much more) that more solitary life.

And then - the next hot summer of 1995 - I had a dry run at an itinerant existence that would last, as it turned out, for a dozen years. I’d had an intensely sociable, even glamorous time in London, hobnobbing with actors, directors, journalists and politicians. I’ve a mental image of myself, just after arriving in (West) London – it was the end of 1981 - at a New Year’s Party. I was dressed in white plimsolls, charcoal grey (school uniform style) trousers and a striped jumper. I must have looked like a liquorice allsort. The party was at the Kinnocks, themselves comparatively new to the capital, a couple very much on the rise. Less than three years later I accompanied Glenys around at the Brighton conference (she needed a minder) after her husband had been elected Labour Leader. It was October time; I wore a short dark donkey jacket, I remember, because she was worried that I looked like Michael Foot at the cenotaph. A few years after that, I favoured a shortie tweed coat bought from Oxfam. ‘Steve, somebody might have died in it,’ she said. Such changes of image (I am maybe being harsh) suggest someone messing round with his persona. And among all this activity I must have carved out plenty of space to write (presumably in jeans, any old jumper or a shirt). Even then I had the feeling that I was more ‘myself’ on my own than in company. At best, I am only intermittently sociable. I sometimes turned attractive invitations down – another New Year party among the glitterati, I remember - even when there was no real need.

In the mid Seventies I’d become a full time writer and needed a fair bit of solitude to get going. The choice in the mid Nineties was more difficult – whether to continue as a writer. In the August heat of’95, I headed to France, my first prolonged visit. I describe it in ‘The House in France.’ What I most remember from that stay are the mornings, the back door open to the garden as I ate breakfast, playing Michael Nyman’s ‘The Piano’ on the CD. No newspapers, the BBC news – if you could get it – crackly at best. A whole day in front of you with nothing to do. I’d felt in the early Nineties that I’d lost my way and after a depressed period had had the experience I’ve attempted to describe in ‘Bumping into God in Kent’ (among the earliest essays on this site). It felt – though the word has unfortunate Blackpool connotations – like an illumination, a call to explore a different way of life. I’ve read explanations about these epiphanies since; they quite often arrive after a period of stress or depression. I find it hard to accept that what happened to me on a May morning in 1995 was somehow self-induced. It still seems to me to be what my friend (Canon) Eric James (see ‘The Beatific Vision’) called the crown of life.

Whatever its origins, it induced a lengthy period of relaxation – a feeling of utter ease I’ve never previously experienced - that summer of ’95. I was care free. I left London, cycling to Charing Cross, loaded the bike on a train, stopped off in Kent, where my friends gave me and the bike (I’m no more a cyclist than I am a footballer) a lift to the Folkestone and the ferry. At Boulogne, with my Lands’ End bag in the pannier, I rode the seventeen miles to my friends’ little house on the crossroads, and lived near self-sufficient for ten weeks before the weather turned and it was finally time to get back to England, cares, duties and what felt like a failing career. There were fires in the evening by then, dark mornings and evenings, a chill round your ankles at the breakfast table.

But a decision had been made. I took next to no advice, though my accountant did say, ‘Don’t sell your flat, Stephen.’ It was fuck it time. I wanted disruption, (a degree of) dis-organisation: you need to be clever to keep the itinerant show on the road. ‘Fuck it,’ said Master Shakespeare, setting off to London to be an actor. ‘Fuck marriage and security,’ as Jane Austen once famously remarked in a letter to her sister, Cassandra, ‘I’m going to write novels.’ ‘Fuck all you fuckers,’ said Vincent Van G (in Dutch: it sounds much the same) setting off for Arles, ‘I’m carrying on painting.’ Most important ‘decisions’ in your life aren’t rational decisions at all. Eventually the writing would come back: I would start selling plays again. And my old charging round London life dropped away – though not completely.

Something else was going on. After May 5, 1995, that climacteric, I started reading theology. I’ve a collection that fills a complete glass fronted bookcase. It’s at the bottom of my bed, though now largely unread: ‘Jesus the Jew’, ‘The Jesuit Mystique’, ‘Zen Catholicism’ and the rest. I could probably have taken a degree. I didn’t find answers – nobody but idiots or fanatics do. Religion is hints and guesswork dressed out; I’ve little time for elaborate concepts like the Holy Trinity. I had a period where I thought of becoming a priest but am glad to say the Church of England has robust (as people say rather than ‘strong’ or ‘vigorous’) procedures for weeding out the delusional. I remember several priests (I’m grateful for their time) warning me off applying in dioceses where the Bishop wasn’t gay friendly. But what finished me was attending an informal meeting of a parish council (which may have been intended to dent my idealism) in South London, hearing the chair, a middle class layman, making snide remarks about that weekend’s Pride event on Clapham Common, an event I had attended the previous day. What was I doing among these bigots?

I now think I was looking for a job. Writing wasn’t paying – or not the writing I wanted to do. And I’ll give myself the credit of not just sitting back watching (not yet quite current) box sets. What I needed to do was to let go the over active search for meaning - answers on a postcard, please - and see what figured, to let the unconscious do the necessarily slow work. So I piddled on. A big commission came in from television. I’d some reputation as a decent researcher and for finding a dramatic way through documentary material. This was a newsworthy, complicated case that I couldn’t see finally making the screen (legally and in other ways) but was worth taking on. I needed to keep my hand in; it kept me occupied and also paid very well - I bought a car on the back of it. It was my last television job and my last script (it was the case of the Saudi Nurses) that ever dealt with social or political issues. That was one of the things that was wrong –or maybe more accurately not quite right - with my writing. People saw me (the Kinnock connection) as a political writer. I earned my money with the Saudi Nurses project, but it would never have been cheap to film, would have offended the Saudi Government, and we – the TV company - would probably have finished up in court with our conclusions. The three scripts were so elaborately praised by the network Head of Drama at ITV (cunt) you just know they’re heading for the slush pile. There was a cheerful concomitant (along with the new £7k Ford Ka). The producer I’d just been happily working with owned a little house in the South West of France, unoccupied. His second wife found it had too many memories of her predecessor. In a pub in Covent Garden one early autumn afternoon, where we ‘repaired’ (as we often did) after a script session, he drew me a very elegant map of how to get there. It was complicated: you doubled back on yourself in a little place called Puy l’Eveque on the Lot and headed north into a forest. The following Spring, after telling my agent that I was out of the game – at least for a time - I set off in my new car down through Western France (and a rainstorm so heavy it caused me to spend a night at one of those magical little places - Uzerche - you occasionally find turning off the main roads in France) to spend what would be six months in the forest.

It was there, working quietly (under a fig tree) that the writing came back – work that I wanted to do, no big budget commercial pressures: a gentle, character based drama, un-earnest but dealing with questions of Christian belief. It was for radio, not much money but enough for my new, more limited, needs. It was the first of three plays for radio that were about priests, would-be priests or monastics. My old friend Eric James had told me more than once that I was a priest (i.e. it was what he wanted for me). This is a man who once prevented Richard Chartres (lately Bishop of London) from giving up on his vocation. Let’s hope he was right about the Bishop, but Eric was wrong about me. Even lately – close on twenty radio plays from that first – I found myself introducing a debate about faith and doubt into a cheerfully rambling narrative. I’ve found no answers but, as they say, have a pretty clear idea of the questions, and that – happily – suits the to and fro of drama.

No pain, no gain. The London housing market escaped me (tough luck: I had near twenty years owning a three bed flat in London, one that even extremely well paid young professionals would find hard to now afford). Some friends fell away. ‘Where are you? Why aren’t you here?’ One or two became irritated with my postcards (later texts) announcing I was back in London for however long it was. Not surprisingly it takes time for folk to catch up with you. You make the call (‘Oh, yes, you said you were back.’). Despite your – and sometimes their - efforts, it’s a slow process of erosion.

I suppose the truth was that I didn’t need their company. Well, solitude is the school of genius – or, in my case, the kind of talent I’d had, that I lost and found again. Anthony Storr, in his book on ‘Solitude’, talks of the present age’s over-idealisation of intimate attachments. That the encouragement to look for complete fulfilment in this way has done more harm than good. His thesis is that you can reach fulfilment without depending on intimate relationships. He also argues that it would be quite wrong to suppose that all those that put their relation with God before their relations to their fellows are abnormal or neurotic - a corrective that pleases me. And – does this bring us back to Brian Clough? – that the high value placed upon shared group feelings is inimical to creativity. It’s not unusual, he observes, for creative people, once they have achieved an intimate relationship, to lose some of their creative drive.

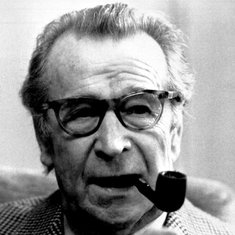

A play I wrote about Flaubert – the start of a long run of plays about artists and writers (‘Adulteries of a Provincial Wife’ in the Listen section) – describes the great man’s fear of intimate attachments. I don’t include the following remark in the play, but when his friend Bouilhet chided him for his distancing of his mistress, Louise Colet, Flaubert said, ‘Yes, but she would enter the study.’ It’s a line that makes me laugh and makes me realise how I’ve run (sometimes not quite keeping up with) my life. There are penalties: occasional loneliness and feelings of isolation. But I’ve always been prepared to pay the price of solitude. The prolific novelist Georges Simenon once said: ‘Writing is not a profession but a vocation of unhappiness.’ But I’ve been happy unhappy, in my fashion.

Stephen Wakelam / June 2017

Let’s assume (in a considerable stretch of imagination) I’m a professional footballer - though retaining my same characteristics and personality. A team bollocking from Brian Clough or Alex Ferguson – yelling, telling you stuff you should know anyway – would be the last thing to get me motivated. I wouldn’t be interested in the team, in any case, apart from their physical attributes. I’m not interested (much) in fame and glory. I would, however, be interested in scoring unusual and perfect goals. I can/do accuse myself of many things but I’ve no interest in money, apart from having enough to keep me going. But it’s my not being a team player interests me. How pop groups stick together more than two weeks bewilders me. Well, the desire to accumulate of oodles of cash no doubt, helps inhibit a break up. And groups of lads – particularly lads – walking round smiling in sync, laughing (inordinately) at one another’s jokes, fill me with something like fond pity. I’m not even very keen on communal displays of grief: ‘coming together’ of the Spirit of Liverpool – or Manchester – variety. And yet, of course, I feel the occasional pull and tug. The film ‘Angel Voices’, written over thirty years ago, shows a boy separating himself from the group – and his regrets.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately of the implications of solitude. The great heat of the last week or so has caused comparisons, first with the summer of 1995, and then – as it got even hotter – with 1976. Both years, I realise, were milestones for me and in both cases retreats from the world. In 1976 I gave up teaching for writing – the pretty cheerful life of the classroom for the study. One of the first jobs I had done with the little house I owned in South Yorkshire was to have a study area made with book shelves, an extension of the living room – the place wasn’t big enough for a separate study. I have a local press photograph of me against a backdrop of books at my Olivetti typewriter, working at a table I still use when writing. Though insecure, ’76 was one of the happiest years of my life. I’d loved teaching but wanted (much more) that more solitary life.

And then - the next hot summer of 1995 - I had a dry run at an itinerant existence that would last, as it turned out, for a dozen years. I’d had an intensely sociable, even glamorous time in London, hobnobbing with actors, directors, journalists and politicians. I’ve a mental image of myself, just after arriving in (West) London – it was the end of 1981 - at a New Year’s Party. I was dressed in white plimsolls, charcoal grey (school uniform style) trousers and a striped jumper. I must have looked like a liquorice allsort. The party was at the Kinnocks, themselves comparatively new to the capital, a couple very much on the rise. Less than three years later I accompanied Glenys around at the Brighton conference (she needed a minder) after her husband had been elected Labour Leader. It was October time; I wore a short dark donkey jacket, I remember, because she was worried that I looked like Michael Foot at the cenotaph. A few years after that, I favoured a shortie tweed coat bought from Oxfam. ‘Steve, somebody might have died in it,’ she said. Such changes of image (I am maybe being harsh) suggest someone messing round with his persona. And among all this activity I must have carved out plenty of space to write (presumably in jeans, any old jumper or a shirt). Even then I had the feeling that I was more ‘myself’ on my own than in company. At best, I am only intermittently sociable. I sometimes turned attractive invitations down – another New Year party among the glitterati, I remember - even when there was no real need.

In the mid Seventies I’d become a full time writer and needed a fair bit of solitude to get going. The choice in the mid Nineties was more difficult – whether to continue as a writer. In the August heat of’95, I headed to France, my first prolonged visit. I describe it in ‘The House in France.’ What I most remember from that stay are the mornings, the back door open to the garden as I ate breakfast, playing Michael Nyman’s ‘The Piano’ on the CD. No newspapers, the BBC news – if you could get it – crackly at best. A whole day in front of you with nothing to do. I’d felt in the early Nineties that I’d lost my way and after a depressed period had had the experience I’ve attempted to describe in ‘Bumping into God in Kent’ (among the earliest essays on this site). It felt – though the word has unfortunate Blackpool connotations – like an illumination, a call to explore a different way of life. I’ve read explanations about these epiphanies since; they quite often arrive after a period of stress or depression. I find it hard to accept that what happened to me on a May morning in 1995 was somehow self-induced. It still seems to me to be what my friend (Canon) Eric James (see ‘The Beatific Vision’) called the crown of life.

Whatever its origins, it induced a lengthy period of relaxation – a feeling of utter ease I’ve never previously experienced - that summer of ’95. I was care free. I left London, cycling to Charing Cross, loaded the bike on a train, stopped off in Kent, where my friends gave me and the bike (I’m no more a cyclist than I am a footballer) a lift to the Folkestone and the ferry. At Boulogne, with my Lands’ End bag in the pannier, I rode the seventeen miles to my friends’ little house on the crossroads, and lived near self-sufficient for ten weeks before the weather turned and it was finally time to get back to England, cares, duties and what felt like a failing career. There were fires in the evening by then, dark mornings and evenings, a chill round your ankles at the breakfast table.

But a decision had been made. I took next to no advice, though my accountant did say, ‘Don’t sell your flat, Stephen.’ It was fuck it time. I wanted disruption, (a degree of) dis-organisation: you need to be clever to keep the itinerant show on the road. ‘Fuck it,’ said Master Shakespeare, setting off to London to be an actor. ‘Fuck marriage and security,’ as Jane Austen once famously remarked in a letter to her sister, Cassandra, ‘I’m going to write novels.’ ‘Fuck all you fuckers,’ said Vincent Van G (in Dutch: it sounds much the same) setting off for Arles, ‘I’m carrying on painting.’ Most important ‘decisions’ in your life aren’t rational decisions at all. Eventually the writing would come back: I would start selling plays again. And my old charging round London life dropped away – though not completely.

Something else was going on. After May 5, 1995, that climacteric, I started reading theology. I’ve a collection that fills a complete glass fronted bookcase. It’s at the bottom of my bed, though now largely unread: ‘Jesus the Jew’, ‘The Jesuit Mystique’, ‘Zen Catholicism’ and the rest. I could probably have taken a degree. I didn’t find answers – nobody but idiots or fanatics do. Religion is hints and guesswork dressed out; I’ve little time for elaborate concepts like the Holy Trinity. I had a period where I thought of becoming a priest but am glad to say the Church of England has robust (as people say rather than ‘strong’ or ‘vigorous’) procedures for weeding out the delusional. I remember several priests (I’m grateful for their time) warning me off applying in dioceses where the Bishop wasn’t gay friendly. But what finished me was attending an informal meeting of a parish council (which may have been intended to dent my idealism) in South London, hearing the chair, a middle class layman, making snide remarks about that weekend’s Pride event on Clapham Common, an event I had attended the previous day. What was I doing among these bigots?

I now think I was looking for a job. Writing wasn’t paying – or not the writing I wanted to do. And I’ll give myself the credit of not just sitting back watching (not yet quite current) box sets. What I needed to do was to let go the over active search for meaning - answers on a postcard, please - and see what figured, to let the unconscious do the necessarily slow work. So I piddled on. A big commission came in from television. I’d some reputation as a decent researcher and for finding a dramatic way through documentary material. This was a newsworthy, complicated case that I couldn’t see finally making the screen (legally and in other ways) but was worth taking on. I needed to keep my hand in; it kept me occupied and also paid very well - I bought a car on the back of it. It was my last television job and my last script (it was the case of the Saudi Nurses) that ever dealt with social or political issues. That was one of the things that was wrong –or maybe more accurately not quite right - with my writing. People saw me (the Kinnock connection) as a political writer. I earned my money with the Saudi Nurses project, but it would never have been cheap to film, would have offended the Saudi Government, and we – the TV company - would probably have finished up in court with our conclusions. The three scripts were so elaborately praised by the network Head of Drama at ITV (cunt) you just know they’re heading for the slush pile. There was a cheerful concomitant (along with the new £7k Ford Ka). The producer I’d just been happily working with owned a little house in the South West of France, unoccupied. His second wife found it had too many memories of her predecessor. In a pub in Covent Garden one early autumn afternoon, where we ‘repaired’ (as we often did) after a script session, he drew me a very elegant map of how to get there. It was complicated: you doubled back on yourself in a little place called Puy l’Eveque on the Lot and headed north into a forest. The following Spring, after telling my agent that I was out of the game – at least for a time - I set off in my new car down through Western France (and a rainstorm so heavy it caused me to spend a night at one of those magical little places - Uzerche - you occasionally find turning off the main roads in France) to spend what would be six months in the forest.

It was there, working quietly (under a fig tree) that the writing came back – work that I wanted to do, no big budget commercial pressures: a gentle, character based drama, un-earnest but dealing with questions of Christian belief. It was for radio, not much money but enough for my new, more limited, needs. It was the first of three plays for radio that were about priests, would-be priests or monastics. My old friend Eric James had told me more than once that I was a priest (i.e. it was what he wanted for me). This is a man who once prevented Richard Chartres (lately Bishop of London) from giving up on his vocation. Let’s hope he was right about the Bishop, but Eric was wrong about me. Even lately – close on twenty radio plays from that first – I found myself introducing a debate about faith and doubt into a cheerfully rambling narrative. I’ve found no answers but, as they say, have a pretty clear idea of the questions, and that – happily – suits the to and fro of drama.

No pain, no gain. The London housing market escaped me (tough luck: I had near twenty years owning a three bed flat in London, one that even extremely well paid young professionals would find hard to now afford). Some friends fell away. ‘Where are you? Why aren’t you here?’ One or two became irritated with my postcards (later texts) announcing I was back in London for however long it was. Not surprisingly it takes time for folk to catch up with you. You make the call (‘Oh, yes, you said you were back.’). Despite your – and sometimes their - efforts, it’s a slow process of erosion.

I suppose the truth was that I didn’t need their company. Well, solitude is the school of genius – or, in my case, the kind of talent I’d had, that I lost and found again. Anthony Storr, in his book on ‘Solitude’, talks of the present age’s over-idealisation of intimate attachments. That the encouragement to look for complete fulfilment in this way has done more harm than good. His thesis is that you can reach fulfilment without depending on intimate relationships. He also argues that it would be quite wrong to suppose that all those that put their relation with God before their relations to their fellows are abnormal or neurotic - a corrective that pleases me. And – does this bring us back to Brian Clough? – that the high value placed upon shared group feelings is inimical to creativity. It’s not unusual, he observes, for creative people, once they have achieved an intimate relationship, to lose some of their creative drive.

A play I wrote about Flaubert – the start of a long run of plays about artists and writers (‘Adulteries of a Provincial Wife’ in the Listen section) – describes the great man’s fear of intimate attachments. I don’t include the following remark in the play, but when his friend Bouilhet chided him for his distancing of his mistress, Louise Colet, Flaubert said, ‘Yes, but she would enter the study.’ It’s a line that makes me laugh and makes me realise how I’ve run (sometimes not quite keeping up with) my life. There are penalties: occasional loneliness and feelings of isolation. But I’ve always been prepared to pay the price of solitude. The prolific novelist Georges Simenon once said: ‘Writing is not a profession but a vocation of unhappiness.’ But I’ve been happy unhappy, in my fashion.

Stephen Wakelam / June 2017