Simon Gray

Simon Gray

IMPURE DRAMA

I've had enough of grim. Denise Gough doing grim. Or Sarah Lancashire. Or Thandie Newton. I watched only ten minutes of the latest 'Line of Duty'; I simply didn’t believe in Thandie Newton as a police officer, seeing only an actress looking glum in a police car. This may be my problem rather than the actress's (I resist the modish all purpose 'actor'). I have the same problem with David Tennant in ‘Broadchurch.’ And yet I believed in him, of course, in a radio play of mine where he represented – for heaven’s sake – a minor 17th century Italian painter, a friend and lover of Caravaggio. What it amounts to is I've had enough of - particularly - police procedurals. If it’s got a body in the first episode, forensics, and there’s a DCI (the preamble makes me laugh) it's the off button; I’m not interested; millions are. (Sergeant) Sarah Lancashire’s home life in ‘Happy Valley’ sounds more than enough to be going on with, surely, without the fag of catching a murderer. And wasn’t Olivia Colman in ‘Broadchurch’ married to the killer? The fact that - impatiently - I’ve barely watched much of any of these series, apart from Thandie Newton looking glum (or unsure of what the script had in store for her, full scripts being, apparently, deliberately withheld from the actors) doesn’t prevent my having views on these matters. (There’s a great line in Simon Gray’s play ‘Butley,’ about an academic, a bit like Gray himself, who says, ‘I hope you realise how it exhausts me to teach books I haven’t read.’). I'm happy to accept ‘Happy Valley’ is ‘incredible,’ and Thandie Newton's character is ‘fascinating’. I’m pissing against the wind, I know. My point is a more general one: it's about grim and glum and gritty. I might actually have watched more than the trailers for ‘Happy Valley’ if I’d known that the villain the harried looking (now BAFTA Best Actress) Sergeant Sarah is trying to nail was played by James Norton. James wasn’t well known when he acted the essayist Montaigne’s secretary in a Radio 3 drama of mine but he almost walked away with the show, having first walked away with the script. What happened was that Peslier, James’ character, completely surprised me in the process of writing the play. We know Montaigne had secretaries, and mine – a young man – just walked unexpectedly into the first scene (he hadn’t featured in any of my synopses). Increasingly he took over, shifting the balance of the piece. There was a plot – Montaigne was on a mission to reconcile murderous opposites in the French Wars of Religion, the fate of the country was at stake and so on - but the whole emphasis of the piece shifted in the writing, away from plot. What looked good on the page in advance (the selling document or synopsis that gets you the go ahead) went background. Derring-do was promised. I delivered on that but the plots and schemes and harum scarums subsided - not exactly background – but taking their place in what had become a character piece. The play described (dread TV phrase) a journey, and a pretty unusual and vital one. But the interest became the developing relationship between Montaigne and his secretary. There are events and obstacles on the way, of course, (but aren't very interesting to script) and, at worse, can easily become one damn thing after another, c.f. 'Lord of the Rings' – the film version. I saw the first part (never to return to the franchise) one cold winter's night at a little 'village' cinema in Fakenham, a meeting room, where they offer you tea and biscuits. I'd been in Norfolk for a week or two, writing and more or less cheerfully isolated, and was looking forward after the film (the only half way decent film on offer my entire stay) to a pint in one of the pleasant looking Fakenham pubs. Sadly, Sean Bean took so long to die, the pubs had closed by the time we came out. Bean played a character called Lurch in a TV play of mine back in the Eighties. When he hit fame a few years later, his biographer rang me. 'He was a very quiet lad,' I said. 'Didn't say anything at all to me. It was only a small part which, I wondered, wasn't big enough for him? Maybe he'd not been enjoying it much.' 'No,' she said, 'It was his first television part. He was terrified.'

And this week, as I write, he's the lead in the new Jimmy McGovern, playing – superbly by all accounts – a Catholic priest. Again, I have to say, it looks grim, folk up against it – as folk are. The title 'Broken' doesn't leave you in much doubt. My film with Sean was called 'Punters,' and like a lot of my stuff was kind-a comic, though I made the mistake of calling it a comedy in advance, which meant those who wanted laugh out loud were disappointed.

I write comedy in its much more general sense, characters I want to live with for however long I takes to write a play. Montaigne (the man and my version of him) has a lot of humour, and balance. And my fictional character, his secretary, Peslier (I took the name from the French jockey) was also wry and teasing. In the closing moments, his master began to see a future role for the secretary, gives him the baton, so to speak, to pass on (I call the next essay ‘Pass it On’). There was the derring-do plot to wrap up, of course, but that was incidental to that subtle shift – a transfer of power which I hadn't seen coming, which became the hinge of the piece. Nor had I guessed the tone of the play would be wry, despite Civil Wars, massacres et al, even (quite) funny – reflecting, I hope, my voice and take on things. I’d found in the course of writing the play what was only half consciously bothering me at the time: my waning physical powers, and that new generation battering at the door.

The BBC (never short of Trump-like bombast these days, continuity announcers assuming their 'important' voice) described it as a ‘major’ play. It wasn’t – I’d call it big-ish. But my preference, any time, is for minor plays. And for a range of tones within a play – Chekhov, not Ibsen. It makes me smile describing my play about working class lads on a betting spree, 'Punters,' as Chekhovian, but that's what I mean by the term comedy. When I attempt the important, the serious – let’s call it the sublime – I fall short. I had a good go in what should have been my heyday at large subjects, principally actuality based – the Guinness trial; the case of the Saudi Nurses. I was paid a great deal of money (for me) by television companies to assemble and master the facts and find a dramatic way through them. Both proved impossible legally. And one of the problems with this kind of docu-drama is by the time you're ready to go – script finished, locations scouted, actors employed, the caravan has moved on. People's attention is elsewhere. I was ready with the three Guinness scripts the week Maxwell fell off his yacht. I also don't have the temperament to be a public 'activist' writer. I've no stomach for controversy, and admire writers who have. I can be quite scrappy, but it's not me. Nor is unrelenting seriousness. I can't keep my face straight, which gets me into trouble in real life every now and again.

The recent Rochdale child abuse drama sounded terrific. There's a whole raft of 'real life' dramas at the moment and I'm glad of that, but couldn't do it for trying any more. We used to have complaints from the right wing press about the validity of 'drama-doc' and 'faction' – really a gripe that the overwhelming majority of these stories show cracks in our society, rather than some Downton view. I was accused with an early drama-doc of mine – 'Gaskin' (Paul McGann in his first big role) - by some recently converted Catholic novelist and 'commentator' of emphasising the seamy side of life. But writing, fast, filming and editing 'Gaskin' was the most thrilling job I've ever had. I'm not great at making things up – I can if pushed but am inclined to feel any fool can make up a plot. I learnt with 'Gaskin' a taste for factually based drama – discovered not imagined material - and would argue that without some factual grit I can't get going these days.

I've also realised that I long for a bit of lightness or contrast within a drama (in my case, a bit of grit, a sliver of ice). Denise Gough, whom I began with, is doing a great line in boredom at the moment in the Conor McPherson. God, she's pissed off. But it's the kind of drama where you're not surprised she has a brother who lives (self imposed distress?) in a garage. I'd prefer a character who breaks the prevailing mood. It's like Graham Greene's novels, the ones he differentiated from his entertainments. From the start we're in Greeneland. No escape. A vulture lands on a roof in the opening page of 'The Heart of the Matter.' You can see where that one's going. Thomas Hardy falls into the same trap with those last two novels of his. Once the horse dies in, what, Chapter Three? it's all downhill for Tess. But these things are, finally, matter of taste, and let's finish this line of 'argument' by saying, with current crop of grim cop dramas (and others), that I blame Scandi-noir for all this.

There may be a correspondence between the prevailing fashion for dark drama and the times we live in. And maybe I'm nostalgic for a kinder pre-Thatcherite world. One of the TV cops I grew up with was Colin Welland ('DB to Z Victor 4. Come in Z Victor 4'), fat and funny, a bit sad, sitting in Z Victor 4 or at least its windscreen against a studio backcloth. Not long before he died, I once sat in the back of a car driven by the real life Welland. He’d become a writer, most famous for ‘Chariots of Fire.’ It’s his ‘Plays for Today’ I best remember – novelistic pieces, not fast paced, but warm, loving. No plot twists. No serial killers, not miserabilist ‘Pure Drama.' People laughed and survived. Welland, as an actor, was memorable in the film of ‘Kes,’a funny film as well as a sad one. lyrical and hard edged. The current Head of Channel Four Drama, as a girl of eight, once sat watching 'Kes' on my VHS while we adults ate and drank in the next room. Her father suddenly realised something, blurting out, 'The kestrel dies' and hurried next door. Too late, Beth was in tears. 'Kes' and the dramas I prefer have shifting tones: impure drama, are character not plot driven. I was glad to be able to tell Welland, on that drive up the Chiswick High Road, how much I had enjoyed his 'Jack Point' – what an influence it had been on me. An amateur operatic company is preparing for a new production, a Gilbert and Sullivan. Who is to tell the long time lead actor that he's not wanted any more? A one off, directed by the great Michael Apted. Indelible. I also remember his 'The Triple Echo' – Glenda at her gruffest. 'Minor' films – and let's have more of them. Fuck franchises. 'Sunday Bloody Sunday', 'The Fabulous Baker Boys', 'Junebug,' 'Breaking Away....'

All are character-y. For five years, in addition to the official curriculum, as a schoolboy actor I inhabited – annually - a different character, playing a run of parts that many decent actors would be thrilled to perform in a lifetime, including, in successive years, Malvolio, Macbeth and Benedick. At Cambridge (it’s maybe what’s you’re there for) I realised I wasn’t quite good enough. I played John Osborne’s ‘Luther’ my first term (would later write a play about Osborne) but hit the glass ceiling with another ‘Brechtian’ play, ‘The Good Woman of Szechwan,’ the following term. I was second choice for the male lead. A guy dropped out and, thereby, did me a favour – though not the one I thought. I was awful, particularly in a drunk scene, knew I was awful, and am now amazed I managed the three or four nights of the run. Stephen Fry (homosexual weed) ran away from a West End production of a Simon Gray play he knew he was bad in, scuppering the whole production. I didn't have the nous to do that. With ‘Good Woman’ I’d realised my limitations and left the boards soon after. I was used to an emotional immersion in the character (let’s raise our game) Stanislavski style or Method Actor-y, which don't help you much with Brechty. Listening to ‘Macbeth’ the other night on the radio, I realised I might have been the most neurotic Macbeth anybody has ever seen. I was 17, and quivering with ambition in the part – as I was in life - from the word go. That same angst had served me well for Osborne’s Luther, who’s constipated (rather over-emphatically) throughout the play. So I was fine playing ‘myself,’ the Jimmy Dean (minus the looks/attitude/ ability) of North East Derbyshire. Dean’s no good in the later stages of ‘Giant,’ where he has to age, the last film he worked on, but, by God, he did whingeing self-pity like nobody's business.

So (as interviewees now say, unnecessarily, at the start of any statement) I became a writer, a bit amazed I’ve survived. No socking great hit, no ‘Kes’ or ‘Chariots of Fire,’ and, in the way of things, it’s some of those that got away – that didn’t get made (like Guinness) you remember as much as the successes. I wanted to call the Guinness sage 'Trouble Brewing' which. I think, shows a certain cast of mind. The title was vetoed and the series put on the slush pile, the biggest disappointment of my writing life.

But I’ve never forgotten the thrill of having my first script accepted – a very gentle three hander - and the read through, at the old ATV Studios in Birmingham, with professional actors (whom – gasp! - I’d seen on the telly). And still look forward to those first full cast gatherings: the introductions (‘I’m Tony Sher and I’m playing Will Shakespeare’), the opening of the scripts (or switching on of tablets these days), your play unfolding. You make a little speech; the actors ask questions, and the play – as it should – begins to escape you. One actor, Edward Fox, in a TV film, asked me to cut the dialogue down: ‘I can do it with a gesture.’ (Was in safe hands, there, mate). Some are humble: Stephen Campbell-Moore: ‘It’s my first radio. You’re going to have to tell me what to do.’ (I didn’t need to). Some are so right for the part – I won’t name them – that you forget you wanted more ‘starry’ actors. But Ken Cranham won’t mind my recounting his saying in the car on the way back from the recording of ‘Answered Prayers’ (which you can hear in the ‘Listen To’ section of this web site): ‘Come on, who was your first choice for this part? Be honest.’) I didn’t tell him Sir Derek was unavailable (or said he was). Ken (later Olivier award winner) was superb in the role, as indeed was James Norton in ‘Living with Princes,’ the Montaigne play, First choice had been Sam Barnett (who was happily later available to play John Osborne in ‘The Author of Myself’). James told me that he lived ‘in somebody’s cupboard’ when working in London. Now you see him, smooth, successful, man-candy, in DJ at awards ceremonies, having, I guess, given up his cupboard-digs.

A few actors I’ve worked with, like Sean Bean, have had stellar careers (despite me), Tom Wilkinson comes to mind – excellent in an adaptation I did, not the main part, cheery and completely ‘un-starry’ on set. Twenty years later it’s Hollywood for Tom. Tim Roth, who’d been having a bad period after early success, was the lead in ‘Coppers,’ what I now think a not very good TV drama I wrote (a slightly fuzzy-focused version available on this site). He was living in Brockley, rather admired my Chiswick flat (we were filming in the area). Next stop - or five years later, at least - he’s on the West Coast, in Tarantino.

I remember with ‘Coppers’ that I was trying to write a kind of ‘King of Comedy’(Scorsese) – both serious and funny - and probably didn’t succeed. But the film is populated by a very talented group of actors, a number of whom I’d worked with at the Royal Court. One or two of them – which is where we started – play policemen. And I suppose, after the slightly sour intro to this essay (and in danger of turning a bit Gwyneth Paltrow), that I want to say how grateful I am to almost all of them. But let’s take the edge off that by mentioning that I worked with one woman, another Royal Court actress, on a stage play (where you’re stuck together for months), whom I would have been very happy never – ever - to see again. Then, last year - after thirty years - in one of those ‘prestige’ dramas on television of a stage play featuring a very, very famous actress (you see if I had written ‘actor’ you'd have even less idea), a face appeared, playing the very, very famous actress’s mother, and I thought, ’She’s familiar,’ before a shiver of recognition and dread – cold fear - ran down my back: ‘I want to talk to you about this part!’ she’d said to me at the previews. I was too wet behind the ears to realise most actors panic before the first try out in front of an audience. It was a production I ran away from (homosexual weed) like Stephen Fry, but I’d started hiding from her before that. The play opened in Sheffield and I then cleared off. Never saw it at the Royal Court in London. It’s when I realised that - unlike the playwright whose play Fry ruined, Simon Gray, and who clearly thrived on the rehearsal process and terrible try-outs, that stage writing is something else that's not quite my thing. I enjoy the quiet of my study (a limitation and strength: I've become, as is obvious from some of the above, a fairly ‘literary’ writer, bookish). Until recently I've had a run of taking a sliver of a life, often a literary or arty figure, and dramatising (getting under their skin) whatever it is I glimpse or think might interest me – E.M.Forster, to take one example, trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and sudden fame.

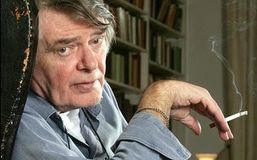

Simon Gray (pictured here: he wasn't as well known as he should have been) is another of my early writer heroes. He may well be at his best, I sometimes think, with his prose memoirs of disasters than with the (stage) plays themselves. I prefer his television work (among a number, 'After Pilkington' and the early 'Spoiled' – a big influence on me) to those stage plays. I wish he’d done more. I once met him at a dinner to which I was invited at an Oxford College. Drink had been taken and I gushed (a fan, at heart) how I admired him. Later, after he began his series of published diaries, I was a bit worried I might appear in a caustic footnote: ‘Like that terrible creep who came up to me once at University College..’ In ‘Enter a Fox,’ which I read recently, Gray recounts how he was told by the director of Faber that he was published by the company only because they wanted to snare Pinter, who had directed many of Simon’s plays. Simon knew his place in the pecking order of playwrights. And Pinter probably, in turn, looked up to Beckett, who's the subject of my latest play. It's what happened to Beckett – or being me, didn't happen – over two weeks in Folkestone in the Spring of 1961. It's kinda funny, fond, not at all bleak. Nobody's lives are changed irrevocably. We’re casting at the moment – a light voiced Irish actor needed, about 55. I’ve three suggestions for the director. Watch this space.

I've had enough of grim. Denise Gough doing grim. Or Sarah Lancashire. Or Thandie Newton. I watched only ten minutes of the latest 'Line of Duty'; I simply didn’t believe in Thandie Newton as a police officer, seeing only an actress looking glum in a police car. This may be my problem rather than the actress's (I resist the modish all purpose 'actor'). I have the same problem with David Tennant in ‘Broadchurch.’ And yet I believed in him, of course, in a radio play of mine where he represented – for heaven’s sake – a minor 17th century Italian painter, a friend and lover of Caravaggio. What it amounts to is I've had enough of - particularly - police procedurals. If it’s got a body in the first episode, forensics, and there’s a DCI (the preamble makes me laugh) it's the off button; I’m not interested; millions are. (Sergeant) Sarah Lancashire’s home life in ‘Happy Valley’ sounds more than enough to be going on with, surely, without the fag of catching a murderer. And wasn’t Olivia Colman in ‘Broadchurch’ married to the killer? The fact that - impatiently - I’ve barely watched much of any of these series, apart from Thandie Newton looking glum (or unsure of what the script had in store for her, full scripts being, apparently, deliberately withheld from the actors) doesn’t prevent my having views on these matters. (There’s a great line in Simon Gray’s play ‘Butley,’ about an academic, a bit like Gray himself, who says, ‘I hope you realise how it exhausts me to teach books I haven’t read.’). I'm happy to accept ‘Happy Valley’ is ‘incredible,’ and Thandie Newton's character is ‘fascinating’. I’m pissing against the wind, I know. My point is a more general one: it's about grim and glum and gritty. I might actually have watched more than the trailers for ‘Happy Valley’ if I’d known that the villain the harried looking (now BAFTA Best Actress) Sergeant Sarah is trying to nail was played by James Norton. James wasn’t well known when he acted the essayist Montaigne’s secretary in a Radio 3 drama of mine but he almost walked away with the show, having first walked away with the script. What happened was that Peslier, James’ character, completely surprised me in the process of writing the play. We know Montaigne had secretaries, and mine – a young man – just walked unexpectedly into the first scene (he hadn’t featured in any of my synopses). Increasingly he took over, shifting the balance of the piece. There was a plot – Montaigne was on a mission to reconcile murderous opposites in the French Wars of Religion, the fate of the country was at stake and so on - but the whole emphasis of the piece shifted in the writing, away from plot. What looked good on the page in advance (the selling document or synopsis that gets you the go ahead) went background. Derring-do was promised. I delivered on that but the plots and schemes and harum scarums subsided - not exactly background – but taking their place in what had become a character piece. The play described (dread TV phrase) a journey, and a pretty unusual and vital one. But the interest became the developing relationship between Montaigne and his secretary. There are events and obstacles on the way, of course, (but aren't very interesting to script) and, at worse, can easily become one damn thing after another, c.f. 'Lord of the Rings' – the film version. I saw the first part (never to return to the franchise) one cold winter's night at a little 'village' cinema in Fakenham, a meeting room, where they offer you tea and biscuits. I'd been in Norfolk for a week or two, writing and more or less cheerfully isolated, and was looking forward after the film (the only half way decent film on offer my entire stay) to a pint in one of the pleasant looking Fakenham pubs. Sadly, Sean Bean took so long to die, the pubs had closed by the time we came out. Bean played a character called Lurch in a TV play of mine back in the Eighties. When he hit fame a few years later, his biographer rang me. 'He was a very quiet lad,' I said. 'Didn't say anything at all to me. It was only a small part which, I wondered, wasn't big enough for him? Maybe he'd not been enjoying it much.' 'No,' she said, 'It was his first television part. He was terrified.'

And this week, as I write, he's the lead in the new Jimmy McGovern, playing – superbly by all accounts – a Catholic priest. Again, I have to say, it looks grim, folk up against it – as folk are. The title 'Broken' doesn't leave you in much doubt. My film with Sean was called 'Punters,' and like a lot of my stuff was kind-a comic, though I made the mistake of calling it a comedy in advance, which meant those who wanted laugh out loud were disappointed.

I write comedy in its much more general sense, characters I want to live with for however long I takes to write a play. Montaigne (the man and my version of him) has a lot of humour, and balance. And my fictional character, his secretary, Peslier (I took the name from the French jockey) was also wry and teasing. In the closing moments, his master began to see a future role for the secretary, gives him the baton, so to speak, to pass on (I call the next essay ‘Pass it On’). There was the derring-do plot to wrap up, of course, but that was incidental to that subtle shift – a transfer of power which I hadn't seen coming, which became the hinge of the piece. Nor had I guessed the tone of the play would be wry, despite Civil Wars, massacres et al, even (quite) funny – reflecting, I hope, my voice and take on things. I’d found in the course of writing the play what was only half consciously bothering me at the time: my waning physical powers, and that new generation battering at the door.

The BBC (never short of Trump-like bombast these days, continuity announcers assuming their 'important' voice) described it as a ‘major’ play. It wasn’t – I’d call it big-ish. But my preference, any time, is for minor plays. And for a range of tones within a play – Chekhov, not Ibsen. It makes me smile describing my play about working class lads on a betting spree, 'Punters,' as Chekhovian, but that's what I mean by the term comedy. When I attempt the important, the serious – let’s call it the sublime – I fall short. I had a good go in what should have been my heyday at large subjects, principally actuality based – the Guinness trial; the case of the Saudi Nurses. I was paid a great deal of money (for me) by television companies to assemble and master the facts and find a dramatic way through them. Both proved impossible legally. And one of the problems with this kind of docu-drama is by the time you're ready to go – script finished, locations scouted, actors employed, the caravan has moved on. People's attention is elsewhere. I was ready with the three Guinness scripts the week Maxwell fell off his yacht. I also don't have the temperament to be a public 'activist' writer. I've no stomach for controversy, and admire writers who have. I can be quite scrappy, but it's not me. Nor is unrelenting seriousness. I can't keep my face straight, which gets me into trouble in real life every now and again.

The recent Rochdale child abuse drama sounded terrific. There's a whole raft of 'real life' dramas at the moment and I'm glad of that, but couldn't do it for trying any more. We used to have complaints from the right wing press about the validity of 'drama-doc' and 'faction' – really a gripe that the overwhelming majority of these stories show cracks in our society, rather than some Downton view. I was accused with an early drama-doc of mine – 'Gaskin' (Paul McGann in his first big role) - by some recently converted Catholic novelist and 'commentator' of emphasising the seamy side of life. But writing, fast, filming and editing 'Gaskin' was the most thrilling job I've ever had. I'm not great at making things up – I can if pushed but am inclined to feel any fool can make up a plot. I learnt with 'Gaskin' a taste for factually based drama – discovered not imagined material - and would argue that without some factual grit I can't get going these days.

I've also realised that I long for a bit of lightness or contrast within a drama (in my case, a bit of grit, a sliver of ice). Denise Gough, whom I began with, is doing a great line in boredom at the moment in the Conor McPherson. God, she's pissed off. But it's the kind of drama where you're not surprised she has a brother who lives (self imposed distress?) in a garage. I'd prefer a character who breaks the prevailing mood. It's like Graham Greene's novels, the ones he differentiated from his entertainments. From the start we're in Greeneland. No escape. A vulture lands on a roof in the opening page of 'The Heart of the Matter.' You can see where that one's going. Thomas Hardy falls into the same trap with those last two novels of his. Once the horse dies in, what, Chapter Three? it's all downhill for Tess. But these things are, finally, matter of taste, and let's finish this line of 'argument' by saying, with current crop of grim cop dramas (and others), that I blame Scandi-noir for all this.

There may be a correspondence between the prevailing fashion for dark drama and the times we live in. And maybe I'm nostalgic for a kinder pre-Thatcherite world. One of the TV cops I grew up with was Colin Welland ('DB to Z Victor 4. Come in Z Victor 4'), fat and funny, a bit sad, sitting in Z Victor 4 or at least its windscreen against a studio backcloth. Not long before he died, I once sat in the back of a car driven by the real life Welland. He’d become a writer, most famous for ‘Chariots of Fire.’ It’s his ‘Plays for Today’ I best remember – novelistic pieces, not fast paced, but warm, loving. No plot twists. No serial killers, not miserabilist ‘Pure Drama.' People laughed and survived. Welland, as an actor, was memorable in the film of ‘Kes,’a funny film as well as a sad one. lyrical and hard edged. The current Head of Channel Four Drama, as a girl of eight, once sat watching 'Kes' on my VHS while we adults ate and drank in the next room. Her father suddenly realised something, blurting out, 'The kestrel dies' and hurried next door. Too late, Beth was in tears. 'Kes' and the dramas I prefer have shifting tones: impure drama, are character not plot driven. I was glad to be able to tell Welland, on that drive up the Chiswick High Road, how much I had enjoyed his 'Jack Point' – what an influence it had been on me. An amateur operatic company is preparing for a new production, a Gilbert and Sullivan. Who is to tell the long time lead actor that he's not wanted any more? A one off, directed by the great Michael Apted. Indelible. I also remember his 'The Triple Echo' – Glenda at her gruffest. 'Minor' films – and let's have more of them. Fuck franchises. 'Sunday Bloody Sunday', 'The Fabulous Baker Boys', 'Junebug,' 'Breaking Away....'

All are character-y. For five years, in addition to the official curriculum, as a schoolboy actor I inhabited – annually - a different character, playing a run of parts that many decent actors would be thrilled to perform in a lifetime, including, in successive years, Malvolio, Macbeth and Benedick. At Cambridge (it’s maybe what’s you’re there for) I realised I wasn’t quite good enough. I played John Osborne’s ‘Luther’ my first term (would later write a play about Osborne) but hit the glass ceiling with another ‘Brechtian’ play, ‘The Good Woman of Szechwan,’ the following term. I was second choice for the male lead. A guy dropped out and, thereby, did me a favour – though not the one I thought. I was awful, particularly in a drunk scene, knew I was awful, and am now amazed I managed the three or four nights of the run. Stephen Fry (homosexual weed) ran away from a West End production of a Simon Gray play he knew he was bad in, scuppering the whole production. I didn't have the nous to do that. With ‘Good Woman’ I’d realised my limitations and left the boards soon after. I was used to an emotional immersion in the character (let’s raise our game) Stanislavski style or Method Actor-y, which don't help you much with Brechty. Listening to ‘Macbeth’ the other night on the radio, I realised I might have been the most neurotic Macbeth anybody has ever seen. I was 17, and quivering with ambition in the part – as I was in life - from the word go. That same angst had served me well for Osborne’s Luther, who’s constipated (rather over-emphatically) throughout the play. So I was fine playing ‘myself,’ the Jimmy Dean (minus the looks/attitude/ ability) of North East Derbyshire. Dean’s no good in the later stages of ‘Giant,’ where he has to age, the last film he worked on, but, by God, he did whingeing self-pity like nobody's business.

So (as interviewees now say, unnecessarily, at the start of any statement) I became a writer, a bit amazed I’ve survived. No socking great hit, no ‘Kes’ or ‘Chariots of Fire,’ and, in the way of things, it’s some of those that got away – that didn’t get made (like Guinness) you remember as much as the successes. I wanted to call the Guinness sage 'Trouble Brewing' which. I think, shows a certain cast of mind. The title was vetoed and the series put on the slush pile, the biggest disappointment of my writing life.

But I’ve never forgotten the thrill of having my first script accepted – a very gentle three hander - and the read through, at the old ATV Studios in Birmingham, with professional actors (whom – gasp! - I’d seen on the telly). And still look forward to those first full cast gatherings: the introductions (‘I’m Tony Sher and I’m playing Will Shakespeare’), the opening of the scripts (or switching on of tablets these days), your play unfolding. You make a little speech; the actors ask questions, and the play – as it should – begins to escape you. One actor, Edward Fox, in a TV film, asked me to cut the dialogue down: ‘I can do it with a gesture.’ (Was in safe hands, there, mate). Some are humble: Stephen Campbell-Moore: ‘It’s my first radio. You’re going to have to tell me what to do.’ (I didn’t need to). Some are so right for the part – I won’t name them – that you forget you wanted more ‘starry’ actors. But Ken Cranham won’t mind my recounting his saying in the car on the way back from the recording of ‘Answered Prayers’ (which you can hear in the ‘Listen To’ section of this web site): ‘Come on, who was your first choice for this part? Be honest.’) I didn’t tell him Sir Derek was unavailable (or said he was). Ken (later Olivier award winner) was superb in the role, as indeed was James Norton in ‘Living with Princes,’ the Montaigne play, First choice had been Sam Barnett (who was happily later available to play John Osborne in ‘The Author of Myself’). James told me that he lived ‘in somebody’s cupboard’ when working in London. Now you see him, smooth, successful, man-candy, in DJ at awards ceremonies, having, I guess, given up his cupboard-digs.

A few actors I’ve worked with, like Sean Bean, have had stellar careers (despite me), Tom Wilkinson comes to mind – excellent in an adaptation I did, not the main part, cheery and completely ‘un-starry’ on set. Twenty years later it’s Hollywood for Tom. Tim Roth, who’d been having a bad period after early success, was the lead in ‘Coppers,’ what I now think a not very good TV drama I wrote (a slightly fuzzy-focused version available on this site). He was living in Brockley, rather admired my Chiswick flat (we were filming in the area). Next stop - or five years later, at least - he’s on the West Coast, in Tarantino.

I remember with ‘Coppers’ that I was trying to write a kind of ‘King of Comedy’(Scorsese) – both serious and funny - and probably didn’t succeed. But the film is populated by a very talented group of actors, a number of whom I’d worked with at the Royal Court. One or two of them – which is where we started – play policemen. And I suppose, after the slightly sour intro to this essay (and in danger of turning a bit Gwyneth Paltrow), that I want to say how grateful I am to almost all of them. But let’s take the edge off that by mentioning that I worked with one woman, another Royal Court actress, on a stage play (where you’re stuck together for months), whom I would have been very happy never – ever - to see again. Then, last year - after thirty years - in one of those ‘prestige’ dramas on television of a stage play featuring a very, very famous actress (you see if I had written ‘actor’ you'd have even less idea), a face appeared, playing the very, very famous actress’s mother, and I thought, ’She’s familiar,’ before a shiver of recognition and dread – cold fear - ran down my back: ‘I want to talk to you about this part!’ she’d said to me at the previews. I was too wet behind the ears to realise most actors panic before the first try out in front of an audience. It was a production I ran away from (homosexual weed) like Stephen Fry, but I’d started hiding from her before that. The play opened in Sheffield and I then cleared off. Never saw it at the Royal Court in London. It’s when I realised that - unlike the playwright whose play Fry ruined, Simon Gray, and who clearly thrived on the rehearsal process and terrible try-outs, that stage writing is something else that's not quite my thing. I enjoy the quiet of my study (a limitation and strength: I've become, as is obvious from some of the above, a fairly ‘literary’ writer, bookish). Until recently I've had a run of taking a sliver of a life, often a literary or arty figure, and dramatising (getting under their skin) whatever it is I glimpse or think might interest me – E.M.Forster, to take one example, trying to come to terms with his homosexuality and sudden fame.

Simon Gray (pictured here: he wasn't as well known as he should have been) is another of my early writer heroes. He may well be at his best, I sometimes think, with his prose memoirs of disasters than with the (stage) plays themselves. I prefer his television work (among a number, 'After Pilkington' and the early 'Spoiled' – a big influence on me) to those stage plays. I wish he’d done more. I once met him at a dinner to which I was invited at an Oxford College. Drink had been taken and I gushed (a fan, at heart) how I admired him. Later, after he began his series of published diaries, I was a bit worried I might appear in a caustic footnote: ‘Like that terrible creep who came up to me once at University College..’ In ‘Enter a Fox,’ which I read recently, Gray recounts how he was told by the director of Faber that he was published by the company only because they wanted to snare Pinter, who had directed many of Simon’s plays. Simon knew his place in the pecking order of playwrights. And Pinter probably, in turn, looked up to Beckett, who's the subject of my latest play. It's what happened to Beckett – or being me, didn't happen – over two weeks in Folkestone in the Spring of 1961. It's kinda funny, fond, not at all bleak. Nobody's lives are changed irrevocably. We’re casting at the moment – a light voiced Irish actor needed, about 55. I’ve three suggestions for the director. Watch this space.