GEORGE MARTIN

Giles Fraser was on ‘Thought for the Day’ this week describing his heart attack, subsequent quadruple by-pass, and hospitalisation on the 7th Floor of St. Thomas’. I was immediately filled with an odd nostalgia for heart attacks, by passes and St. Thomas’ - for what was the most intense period of my life, I suppose. The fact that I know how the plot turned out (so far) helps. I like the Rev. Giles. He writes homilies the way I write essays: despite his best Christian efforts, everything revolves round himself. I do wish he’d not once offered us the fact that he was circumcised. I have a tendency to imagine men’s dicks and it gets in the way of what he’s saying, though I think - in fairness – the information was related to his Jewish ancestry. (This morning’s ‘Thought for the Day’ featured the Chief Rabbi and got the usual switch off from me – guess why? Though it’s not just him: the Archbishop of Canterbury was at it again this week, hand wringing about homosexuality: ‘What do you expect me to say?’ when asked if gay sex was immoral.) But Giles seems a friend of gays. My old friend Eric James was once asked to preach at his church. In the vestry afterwards Giles lit up. ‘What are you doing smoking?’ Eric burst out (as he could). ‘You have your children to think about.’ I presume he has packed in smoking now. There is the air of the motorcycling vicar about Giles. He sounds as if he could be trouble if pushed: he certainly stirred things up at St. Paul’s Cathedral, not his natural habitat you think. He probably enjoys knocking round in media circles a bit too much, maybe likes more than ‘a dry sherry, vicar’. But he registered for me through an article he wrote in the Guardian – before he became well known (at least to Radio 4 audiences) – the best piece on the Resurrection I’ve come across.

I don’t remember if that was his theme with the heart attack ‘Thought for the Day’ – more something to do with St. Paul and clay vessels I didn’t understand. His line on the Resurrection, in David Jenkins’, former Bishop of Durham’s vivid phrasing, was that it’s more than a conjuring trick with old bones. The disciples don’t recognise the risen Jesus, and see him differently, even confusedly. The fact that the experiences are so different, not orchestrated by the Gospel writers into a coherent stunning revelatory sound and light show, adds to the authenticity of what seems to have happened to individuals and groups in in those years after Jesus’ death. I think what it comes down to is that you experience the risen Christ within you. It continues to happen even far from that little neck of the Middle East, people seeing ‘the truth and the light.’

I’ve experienced it in my life, over twenty years ago now: see Bumping into God in Kent. And feel, this last year or two, resurrected in a different way. Knowing I had a serious life threatening illness people still ask – three years on - ‘Are you OK?’ Or, regularly, after a quick glance, ‘You look well.’ The (physically) resurrected Stephen is back to his old weight, having lost a near quarter of my body weight at one point: ‘You looked …well, frail,’ said one young friend recently. I’m not transformed in a religious sense, am no less self absorbed (arguably even more so), am still intermittently and inconveniently randy as my powers fade etc, ‘same old story, same old act’ (Springsteen, who knew, on the basis of his interesting, self-flagellating autobiography, what he was talking about). I’ve tried to map some of my own daftness in these essays, on the assumption that any reader, even if not an introverted gay with a half dead heart, will recognise equivalent symptoms in him - or herself. (I’m glad I’ll be dead by the time ‘binary’ indicators are against the law).

Clearly on my last lap, I spend a great deal of time these days, like some ancient in front of the fire (one of Shakespeare’s ‘spinsters and knitters in the sun’) rifling through memories, images – I can spend hours doing this: only yesterday – surfacing like some lost computer file - remembering three Cambridge male students (one me), in a pub opposite Queens’ College, paying court to the most stunning woman I had met to that point, Sue Limb of Newnham. I’ve never met Sue since, and no idea why she flashed up the other day. We both finished up as radio writers, oddly – hard to envisage in 1966. I’ve also been thinking back to Rigal, a tiny settlement in the forest just north of the Lot, where I spent a glorious (if isolated) six months at the turn of the century and where my ability to write (at least write someway decent stuff) came back, with a – modest - radio play. It’s an image of my sitting, biblically, under a fig tree (as happened). I’ve described it elsewhere: getting my mojo back was a kind of resurrection in its way. But seventeen years on from the fig tree at the bottom of stone steps - the crumbling home to geckos - I’ve lost the urge to write, which is quite different from losing the ability to. A period – not unhappy, though not at the peak of Fortune’s bonnet either – of torpor. No desire to pick up my pen, or head to the computer to write. Or, more precisely, I’ve lost the impetus to write what I’ve been writing most of this century, plays for radio, which seem to have come along regularly like planes into Heathrow. Essays have filled (too many metaphors) my sky. I’ve been thinking – deliberately flirting - with retirement. It’s surfacing in the earliest essays in this batch (lunchtime drink - maybe two; a bit of gardening). There was a play in the works, which helped, so if anyone asked this summer what I was up to, I had the line; ‘Yes, I’ve got a play on in September.’ It went out a few days ago (so no alibi left). I’d got quite glum about it – who’s interested in a play about Samuel Beckett holing up at an off season seaside hotel? But it got a cheering response – or at least as much notice as radio plays get ; ‘Pick of the Day’ all over the place, and little puffs for me, making me feel like a low to middle order batsman who’s just scored a century. They played the climactic scene of the play on Radio 4’s ‘Pick of the Week’ on Sunday. It’s a very quiet ‘big’ scene, contrasting I couldn’t help thinking with the husband and wife prowling and shagging in the kitchen in ‘Doctor Foster.’ I’d watched this episode out of context, having not seen the rest of it, and rather admired its bravura, while reflecting – yet again – that I couldn’t write anything like that if you paid me (and with my track record you wouldn’t). I started this series with an essay I was a bit reluctant to post at first called Impure Drama, detailing the kind of drama I like as opposed to what’s mainly on offer. I’m not a television writer anymore and was afraid it would be seen as sour grapes. But, at the risk of sounding like those folk who want more good news, I’d had enough of the grimness of contemporary TV drama, so was pleased that, subsequently, the Head of BBC TV Drama at the Edinburgh Film Festival, announced a welcome diminution of grimness.

Bleakness - confrontational drama, folk at one another’s throat (or other orifices (c.f. ‘Dr. Foster) - plays well in trailers, of course, and I notice, sadly, that before the broadcast of my play about Beckett the preceding continuity announcements were for TV ‘Pure Drama’ (in that urgent, nudge-nudge, ‘dontcha leurve it’ tone) and for a radio re-tread of a Ray Connolly film. But I mustn’t get bitter and twisted. No writer is ever happy with the promotion of their work (ungrammatical; non binary!). Unless you’re Alan Hollinghurst. All summer long the Guardian has been advertising a lecture by the great man, staring at us a bit balefully: a particular event, a fixed venue. And you think, how many people can this hall hold? (I’ve also gone off the Guardian this summer, but we won’t worry about that). I look forward to the new Hollinghurst, though haven’t pre-ordered it as with his last, ‘The Stranger’s Child,’ a novel which necessitated a brisk walk on finishing it - to shake off its brilliance. I almost jacked in writing back then in 2011 in awe, managing to carry on writing in my own fashion afterwards, through employing such arguments as ‘well, it’s possibly just a bit overwritten,’ ‘bit hifalutin,’ ‘can’t see the wood, sometimes, for the trees,’ clutching at straws and reminding myself, again/again, that writing is not a competitive sport. Thankfully Hollinghurst takes at least half a decade between novels, so those left in his wake have time to re-group. Having had a good go lately with my own attempts at fiction, and reluctantly deciding to jettison it and start all over again, I do wish his timing with ‘The Sparsholt Affair’ was a bit different, but I expect, along the line, he scraps no end.

There’s a great line of Chekhov’s, I think - if it’s not it sounds like him. It goes something like this: ‘I’m not disappointed, I’m not tired, I’m not depressed. It’s simply that everything has become less interesting.’ Which has been the case with me, no doubt a let-down (is the only word) after the thrills and spills of a heart operation and the stages of recovery, hurdles overcome, and that I’m back jog trotting again. Along with the knowledge that, try as I might, I’m running down. ‘I think this play is my swan song,’ I’ve been saying all summer. ‘But you’ve only just got going!’ is the response (untrue). ‘You can’t not write.’ Yes, I can. ‘You mustn’t stop writing.’ (I’m not making these quotes up: proof on file). Maybe what friends have spotted more sharply than me is that I’m probably defined by writing. I was aiming at a small target with the latest play, but seem to have bullseyed it (as opposed to ballsing it up). It’s not a bad one to go out on. A friend described it as ‘aslant’ which I like. I need some scrap of info or unusual angle to head into a subject, almost always a real person these days with me. The usual dramatic standbys of adultery, alcoholism, sexual secrets, cruelty to children etc. just don’t do it. And people kept on listening, ‘absorbed’, even though there was next to no plot. You can keep a piece like that moving along through a springy rhythm, some variety of voices and scenes. When I listened, after a gap since the recording in July, I wasn’t always sure what the next scene was; a good sign. And the play, as another pal indicated, is much more about the girl receptionist at the hotel where Samuel Beckett stayed (incognito) than about the writer himself. Another said, ‘Well you’re there in all three main characters: as the ambitious student, as the teacher and as the ‘wise’ older writer, Beckett,’ which I found faintly worrying. I know I’m wrapped up in myself, but thought I was creating characters. This perceptive pal (a former TV producer) liked the fact that stuff (or not too much) wasn’t spelt out, that he had to join up the dots. The pressure is almost inevitably for you to up the ante these days. Which I mainly resist, being old in the tooth and set in my ways. ‘He never gives you the big scene head on,’ the producer of the TV film ‘Angel Voices’ once said, getting me to heighten the confrontation near the end between the Head Chorister and the Choirmaster (she was right to do so in that instance). I don’t really do ding dong is what it amounts to, for better or worse. I like the way Henry James in ‘Portrait of a Lady’ cuts away from Isabel’s discovery of the horror of her marriage, not taking the obvious more direct approach. It was a book I used to love, and I think influenced me. And Jane Austen didn’t bother, either….‘let other pens dwell on guilt and misery.’

And even with essays like this I only seem to get going tangentially - Giles Fraser and we’re off. I started an essay about a month ago with a definite subject, about film-going (with a note of my enchanted Chesterfield childhood thrown in, and a bit about my mum, who gets shorter shrift in these essays than she merits. She loved the pictures, kicking off something in me. So let’s give her and the flicks a go. The piece started like this:

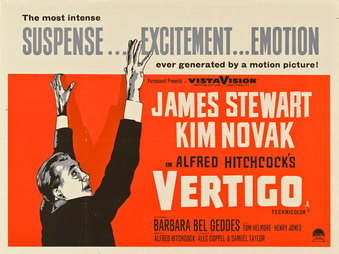

On my way to and from school when I was a little kid was a little enclave – I don’t know the word for it – backwater? - a cobbler’s in a sizeable wooden hut (I can still smell its interior) at its entrance, a blacksmith’s a bit further in, where we would stop to watch horses being shod. Beyond, along what wasn’t a properly made up road, were little Victorian cottages with pretty rockery style gardens immediately outside their front doors. This little street – track - was immediately adjacent to a railway line in a deep cutting behind a high smoke blackened wall. (This whole area was razed in the Seventies to make way for Chesterfield’s ring road). With other kids I used to clamber this wall and walk along it. There was a drop the other side that would have killed you, which was why we did it, of course. One morning our Junior School Headmistress, Miss Jones, a formidable woman, announced at school assembly: ‘It has been reported to me..’ demanding those who had been walking this walk to come to the front. I was the only one to do so (the honourable schoolboy?), shamefaced, blushing. Not a bad tactic, actually. I finally received a form of praise: ‘Well, Stephen has been the only honest boy..’ But what I remember about that long gone enclave, most of all, are the cinema posters – quite modest in size – on display at its entrance opposite the cobbler’s, and which I viewed daily coming back and fro from school. ‘The Man with the Golden Arm,’ I remember in particular. I didn’t know what a golden arm was, though it didn’t sound very pleasant – and the film was certificated beyond my, then, six years. I still remember Frank Sinatra as one of the actors (I’d thought him just a singer). There were other faces on the poster, a little line of its stars, which meant it would have been the first time I noticed Kim Novak.

I now know that a year or so later she was in ‘Pal Joey,’ (another film I saw a poster for). This is because I looked her up last night, half way through one of my regular viewings of the film by which she is best remembered – ‘Vertigo.’ This masterpiece barely makes sense on plot level: it’s ‘tosh’ – as a friend said to me back in the Eighties. I’d taken her to it; the film had just surfaced having been next to unavailable (there were occasional bootleg reported late night showings). Back in circulation with specially cleaned up print after near thirty years since I’d first seen it with my mum (I was 10) I took the first opportunity to re-visit the film (certain images of which I retained) at a matinee one West London mid-week afternoon. I wasn’t the only one eager to see it. The playwright Christopher Hampton was sitting behind me. I swooned through it all over again – it’s a kind of rhapsody of romantic longing with a thriller plot- and went back to see it with my (‘it’s tosh’) friend the following day. The plot is tosh, but it’s not the (bizarre) plot that carries it, but its atmosphere…

Now the problem with that - so far as these essays go - was it was a bit worked up. Something else - a different form of writing – is going on there. What I had intended to do with what would have been the thirteenth essay (I was aiming for fourteen, like the tracks on a Beatles’ LP) was then ramble a bit about movies I’d seen from ‘The Greatest Show on Earth,’ the first I remember. It has a rail crash which gave a five year old nightmares; there’s what I recall as a blue flash and then the circus animals escape from the trucks. That would have led me to certain images from ‘Vertigo’ which never left me during that thirty year gap. Impossible to imagine, these days, a film disappearing for so long. When I went to San Francisco, where the film is set, I did a ‘Vertigo’ tour of its locations, a bit nutty, working it out for myself (there are now official tours). I discovered that in the church where Jimmy Stewart follows Kim Novak out into the graveyard in that early hypnotic chase sequence, in reality the door leads into a closed vestry. Hitchcock puts a filter on the film for the subsequent near silent, ravishingly beautiful graveyard sequence (just the clicking of footsteps) where Novak visits her ‘predecessor’ Carlotta Valdes’ grave. Novak’s is a terrific performance, in a very tricky role and I would later have noted that, many years later, 2012, I think, I would meet an actor at a BBC reception I didn’t recognise at first - a benign and still handsome old man who introduced himself to me (we were early) and got chatting. He was Richard Johnson, who it turns out (I learnt it only last month looking up Novak) was once Kim’s husband. So there we are – one handshake away from an actress who once appeared so impossibly distant (even more unattainable that the 19 year old Sue Limb). It was Novak in receipt of that famous line from Hitchcock (he had wanted someone else for the role); seeking ‘motivation’ for her twin characters, she was told, ‘It’s only a film Miss Novak.’

Mum and I used to talk about the films as we headed back from town home down Hollis Lane. My dad’s regime of shifts meant he would be in bed or at work and I remember only once going with him to the pics. Another Hitchcock: the great ‘North by North West’. We waited in the foyer before the film for the manager to come down, who then let us in for free: my dad being the town’s police inspector (some small town trade off). After the breathless ‘NBNW’ (which I once recorded on an audio tape recorder from the television in the days before VHS – or readily available scripts - to see how it worked) we went for plaice, chips and peas in the cinema’s restaurant, with bread and butter (maybe margarine?) and a pot of tea. They were the happiest three/four hours of my life: it was 1959, I was 12…..

Which is all right if verging on the lyrical, but a bit too formally autobiographical (the writer’s early life), threading past and present; that was then and this is how far we have come. I know what I’m doing, though – and I like a few more surprises, both in playwriting and essays. ‘Where is this taking me?’/ ‘Oh, that’s what it’s about.’ And ‘lyrical’ accounts of other people’s childhood bore me (even Tolstoy’s). As my old History teacher said, having recently read the previous dozen essays: ‘Come on, you’re a little boy from Piccadilly Road (see Piccadilly) who’s moved in all sorts of exalted circles and met a remarkable range of people in so many different situations. Twist it into a long story aka a novel.’ He’s regarded these essays for some time as a dry run at a longer form of fiction. He also, incidentally, bemoans my emphasis on gay promiscuity: ‘You’ve been there long enough.’ I’m also amused at the way he hints a preference for my earlier more succinct style of essay writing (‘like your essay for me about the coming of the railways in the 19th century’).

In short, as Mr. Bennet once advised his modestly talented third daughter, who had spent too long at the piano: ‘Thank you, Mary. You have entertained us long enough.’ It’s possible I’ll get Proustian and autobiographical in a different format (though doubt it): the smell of urine and disinfectant in public lavatories, perhaps, summoning up a host – a haze - of fond memories. I neglected to say when I did describe cottaging in an earlier essay that, just after I arrived in London, I met the great (late) director Bill Gaskell who was in conversation with another distinguished director (still extant). They were regretting the closing of some well-known London pissoirs. Fresh faced me (it now makes me laugh) was a bit surprised and disappointed. I’d expected them to be discussing Harley Granville Barker or Osborne.

I’ve wanted to describe, under various ‘topics’ - as the mood or inclination takes me – how I’ve felt this summer, having moved into what’s surely my last house. There’s a crochettiness has kept coming through. But it’s the way I am – increasingly like some eccentric who’s moved into Richmal Crompton’s William Brown’s village. If William was listening outside my door the other night he would have heard me yelling out ‘like!’ every time a young woman on the radio kept littering her sentences: ‘like…like…like.’ William, implausibly innocent of sex, probably wouldn’t register an embarrassing eroticism that keeps surfacing in a number of the essays. But I cheer myself with the journals of John Cheever, another elderly gent, and his (cheerfully depressive) musings: ‘I may fall in love with a lonely grocery boy. A gentle heart and a capricious cock.’ Update that for Deliveroo with me. And I don’t forget how the great John Maynard Keynes (they didn’t teach me this in economics at school) once looked lasciviously down from high table in Cambridge, at the - male - undergraduates with intentions that would have had him arrested then or now.

I’ve been much taken with the film ‘God’s Own Country’ lately (which has quite a bit of the man on man I like - and features cottaging). I saw it three times in two weeks - not for the cottaging: it’s a masterpiece. Josh O’Connor, who plays the lead, is drunkenly despairing in the opening sequences of the film, though breaks out of his emotional numbness by the end. It’s an astonishing performance in which he also runs a dialogue scene completely bollock naked (worth the price of a couple of cinema tickets). A friend, who’s known me for forty years, after hearing of my triple trip to the cinema, wondered why: ‘I’ve never seen a film three times.’ I had to come clean and texted saying that the buried emotion and need in the film struck a chord with me. ‘It’s the buried theme in most of your web essays,’ he replied. Another friend, who’s known me since school, had said previously, in relation to Father’s Day (which had moved him): ‘Well losing your father when you did must have had its effect, as well as making you more resilient.’ I’ve always assumed that, on the whole, my emotional sights are set pretty low. But this form of writing is, surprisingly, just like a play in which people come to conclusions, judge, discriminate. And, as with a play – sometimes years after the event - you learn something about yourself. Analysts (I believe) encourage their patients in a stream of consciousness, where the true subject – the problem, knot or inhibition - eventually bubbles up. I’ve tidied and smoothed the odd transition after writing, but these pieces have been pretty free flowing, crustiness and all; a lot angrier about society’s treatment of homosexuality than I imagined, and quite possibly revealing more yearning for intimacy/affection than I normally credit myself with. There’s a lot of ‘if only’ about them. Well, it’s a bit too late in the day for the full (Love Island) number. And all my parts, sadly, aren’t in - how shall I put it? - Josh O’Connor order. I’m not very keen, as I say in the introduction to a sidelined novel, with what often blows in with love. Possessiveness. Jealousy. When last infatuated I finished up punching the loved one. But I also remember the feeling at that time of also being in love with the whole world.

So there it is: ‘if only.’ You wonder if you’ve missed the point of life – though just when I was feeling a bit maudlin about not loving enough I read that there’s a new movement called ‘sologamy’- mainly women who go through public ceremonies marrying themselves. This is a very encouraging development, though notice that the girls go to the expense of buying wedding dresses and rings. I think I had my own secret (cheap as muck) ceremony quite a few years ago now. Made my bed, lay on it. Eric James, my priest friend, with whom I’d talk of these things, said – he was also talking about himself – ‘Well, you’ve made more of your friends as a result.’ I texted one of those friends over the weekend, a racing pal, an ex-student of mine, having done the rounds of the major race meetings by bike this autumn and currently living in a tent close to Chantilly racecourse,. I was once pretty sold on this handsome fellow – who sadly hasn’t a gay bone in his body. (When he told his mother I was gay she said, ‘I know.’ ‘How do you know?’ ‘He said he admired my curtains.’)

Well, John got married (young). The marriage went wrong and he was very unhappy for a time. ‘You know how to live on your own, Steve,’ he said. ‘You like it. I don‘t.’ I’m not sure I always do but have got used to it, though there are the usual anxieties about increasing frailty. I mentioned to him lately about this desire of mine to maybe give up, live a little more, change my life a bit, work less - be more ‘receptive to experience’ as another priest pal suggests. John, somewhere in France (a Latinist, ‘Gaul’ he likes to call it) replied by reminding me that his dad had died six weeks after retiring, aged 70, on his first proper holiday in Blackpool. And I must say, honestly, I fancy my friend’s heroic autumn journey (Leopardstown via Newmarket, Doncaster and Chantilly), more than finding someone to step into the sunset with….but I couldn’t do the hills: I’ve got lately to thinking about an electric bike. Oh, dear. As Natasha Kinski bemoaned, with her best Polish accent, in ‘Tess of the D’Urbervilles’: ‘It’s too la-yte, Angel. It’s too la-yte.’

I started these latest essays in April (before the 2000 Guineas – see Pass It On) and it’s now the weekend of the Arc de Triomphe, still just about sunny and warm. John, in Gaul, with ground sheet presumably, is hoping for good ground for his 16-1 fancy. But there was a shower of rain this morning, the heating is beginning to creak on in the house I’ve lately settled into. A bit of fiction’s got abandoned this summer, a play was recorded, these essays – herewith - brought to a close (with thirteen tracks - though this last one’s a bit of a double number). I’ve found the freewheeling essay form satisfying and want to get some of its breeziness- rapid, light brushstrokes/going forwards, back, sideways at will - into my fiction writing, if I can, without losing the traditional virtues of the novel: an engaging narrative, fully rounded characters. John Lennon told George Martin that he wanted ’Strawberry Fields’ to be both ‘fast and slow at the same time.’ I could do with a resident George.

The last Beatles’ LP – also ending with a bumper compilation of bits and bobs - tailed off with Paul at his most upbeat: ‘And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.’ I don’t think I can manage to live up to that injunction (and the Beatles at that time, I note, were at daggers drawn) so will settle for a line I picked up from somewhere – a newspaper article, if memory serves, some Christian commentator, probably - about God’s assurance that our ludicrous inability to be who we want to be is ultimately forgiveable and forgiven. ‘Was he a disappointed man?’ the novel I was writing begins. ‘Or just getting old?’ Just getting old, I think. (October 2017)

Giles Fraser was on ‘Thought for the Day’ this week describing his heart attack, subsequent quadruple by-pass, and hospitalisation on the 7th Floor of St. Thomas’. I was immediately filled with an odd nostalgia for heart attacks, by passes and St. Thomas’ - for what was the most intense period of my life, I suppose. The fact that I know how the plot turned out (so far) helps. I like the Rev. Giles. He writes homilies the way I write essays: despite his best Christian efforts, everything revolves round himself. I do wish he’d not once offered us the fact that he was circumcised. I have a tendency to imagine men’s dicks and it gets in the way of what he’s saying, though I think - in fairness – the information was related to his Jewish ancestry. (This morning’s ‘Thought for the Day’ featured the Chief Rabbi and got the usual switch off from me – guess why? Though it’s not just him: the Archbishop of Canterbury was at it again this week, hand wringing about homosexuality: ‘What do you expect me to say?’ when asked if gay sex was immoral.) But Giles seems a friend of gays. My old friend Eric James was once asked to preach at his church. In the vestry afterwards Giles lit up. ‘What are you doing smoking?’ Eric burst out (as he could). ‘You have your children to think about.’ I presume he has packed in smoking now. There is the air of the motorcycling vicar about Giles. He sounds as if he could be trouble if pushed: he certainly stirred things up at St. Paul’s Cathedral, not his natural habitat you think. He probably enjoys knocking round in media circles a bit too much, maybe likes more than ‘a dry sherry, vicar’. But he registered for me through an article he wrote in the Guardian – before he became well known (at least to Radio 4 audiences) – the best piece on the Resurrection I’ve come across.

I don’t remember if that was his theme with the heart attack ‘Thought for the Day’ – more something to do with St. Paul and clay vessels I didn’t understand. His line on the Resurrection, in David Jenkins’, former Bishop of Durham’s vivid phrasing, was that it’s more than a conjuring trick with old bones. The disciples don’t recognise the risen Jesus, and see him differently, even confusedly. The fact that the experiences are so different, not orchestrated by the Gospel writers into a coherent stunning revelatory sound and light show, adds to the authenticity of what seems to have happened to individuals and groups in in those years after Jesus’ death. I think what it comes down to is that you experience the risen Christ within you. It continues to happen even far from that little neck of the Middle East, people seeing ‘the truth and the light.’

I’ve experienced it in my life, over twenty years ago now: see Bumping into God in Kent. And feel, this last year or two, resurrected in a different way. Knowing I had a serious life threatening illness people still ask – three years on - ‘Are you OK?’ Or, regularly, after a quick glance, ‘You look well.’ The (physically) resurrected Stephen is back to his old weight, having lost a near quarter of my body weight at one point: ‘You looked …well, frail,’ said one young friend recently. I’m not transformed in a religious sense, am no less self absorbed (arguably even more so), am still intermittently and inconveniently randy as my powers fade etc, ‘same old story, same old act’ (Springsteen, who knew, on the basis of his interesting, self-flagellating autobiography, what he was talking about). I’ve tried to map some of my own daftness in these essays, on the assumption that any reader, even if not an introverted gay with a half dead heart, will recognise equivalent symptoms in him - or herself. (I’m glad I’ll be dead by the time ‘binary’ indicators are against the law).

Clearly on my last lap, I spend a great deal of time these days, like some ancient in front of the fire (one of Shakespeare’s ‘spinsters and knitters in the sun’) rifling through memories, images – I can spend hours doing this: only yesterday – surfacing like some lost computer file - remembering three Cambridge male students (one me), in a pub opposite Queens’ College, paying court to the most stunning woman I had met to that point, Sue Limb of Newnham. I’ve never met Sue since, and no idea why she flashed up the other day. We both finished up as radio writers, oddly – hard to envisage in 1966. I’ve also been thinking back to Rigal, a tiny settlement in the forest just north of the Lot, where I spent a glorious (if isolated) six months at the turn of the century and where my ability to write (at least write someway decent stuff) came back, with a – modest - radio play. It’s an image of my sitting, biblically, under a fig tree (as happened). I’ve described it elsewhere: getting my mojo back was a kind of resurrection in its way. But seventeen years on from the fig tree at the bottom of stone steps - the crumbling home to geckos - I’ve lost the urge to write, which is quite different from losing the ability to. A period – not unhappy, though not at the peak of Fortune’s bonnet either – of torpor. No desire to pick up my pen, or head to the computer to write. Or, more precisely, I’ve lost the impetus to write what I’ve been writing most of this century, plays for radio, which seem to have come along regularly like planes into Heathrow. Essays have filled (too many metaphors) my sky. I’ve been thinking – deliberately flirting - with retirement. It’s surfacing in the earliest essays in this batch (lunchtime drink - maybe two; a bit of gardening). There was a play in the works, which helped, so if anyone asked this summer what I was up to, I had the line; ‘Yes, I’ve got a play on in September.’ It went out a few days ago (so no alibi left). I’d got quite glum about it – who’s interested in a play about Samuel Beckett holing up at an off season seaside hotel? But it got a cheering response – or at least as much notice as radio plays get ; ‘Pick of the Day’ all over the place, and little puffs for me, making me feel like a low to middle order batsman who’s just scored a century. They played the climactic scene of the play on Radio 4’s ‘Pick of the Week’ on Sunday. It’s a very quiet ‘big’ scene, contrasting I couldn’t help thinking with the husband and wife prowling and shagging in the kitchen in ‘Doctor Foster.’ I’d watched this episode out of context, having not seen the rest of it, and rather admired its bravura, while reflecting – yet again – that I couldn’t write anything like that if you paid me (and with my track record you wouldn’t). I started this series with an essay I was a bit reluctant to post at first called Impure Drama, detailing the kind of drama I like as opposed to what’s mainly on offer. I’m not a television writer anymore and was afraid it would be seen as sour grapes. But, at the risk of sounding like those folk who want more good news, I’d had enough of the grimness of contemporary TV drama, so was pleased that, subsequently, the Head of BBC TV Drama at the Edinburgh Film Festival, announced a welcome diminution of grimness.

Bleakness - confrontational drama, folk at one another’s throat (or other orifices (c.f. ‘Dr. Foster) - plays well in trailers, of course, and I notice, sadly, that before the broadcast of my play about Beckett the preceding continuity announcements were for TV ‘Pure Drama’ (in that urgent, nudge-nudge, ‘dontcha leurve it’ tone) and for a radio re-tread of a Ray Connolly film. But I mustn’t get bitter and twisted. No writer is ever happy with the promotion of their work (ungrammatical; non binary!). Unless you’re Alan Hollinghurst. All summer long the Guardian has been advertising a lecture by the great man, staring at us a bit balefully: a particular event, a fixed venue. And you think, how many people can this hall hold? (I’ve also gone off the Guardian this summer, but we won’t worry about that). I look forward to the new Hollinghurst, though haven’t pre-ordered it as with his last, ‘The Stranger’s Child,’ a novel which necessitated a brisk walk on finishing it - to shake off its brilliance. I almost jacked in writing back then in 2011 in awe, managing to carry on writing in my own fashion afterwards, through employing such arguments as ‘well, it’s possibly just a bit overwritten,’ ‘bit hifalutin,’ ‘can’t see the wood, sometimes, for the trees,’ clutching at straws and reminding myself, again/again, that writing is not a competitive sport. Thankfully Hollinghurst takes at least half a decade between novels, so those left in his wake have time to re-group. Having had a good go lately with my own attempts at fiction, and reluctantly deciding to jettison it and start all over again, I do wish his timing with ‘The Sparsholt Affair’ was a bit different, but I expect, along the line, he scraps no end.

There’s a great line of Chekhov’s, I think - if it’s not it sounds like him. It goes something like this: ‘I’m not disappointed, I’m not tired, I’m not depressed. It’s simply that everything has become less interesting.’ Which has been the case with me, no doubt a let-down (is the only word) after the thrills and spills of a heart operation and the stages of recovery, hurdles overcome, and that I’m back jog trotting again. Along with the knowledge that, try as I might, I’m running down. ‘I think this play is my swan song,’ I’ve been saying all summer. ‘But you’ve only just got going!’ is the response (untrue). ‘You can’t not write.’ Yes, I can. ‘You mustn’t stop writing.’ (I’m not making these quotes up: proof on file). Maybe what friends have spotted more sharply than me is that I’m probably defined by writing. I was aiming at a small target with the latest play, but seem to have bullseyed it (as opposed to ballsing it up). It’s not a bad one to go out on. A friend described it as ‘aslant’ which I like. I need some scrap of info or unusual angle to head into a subject, almost always a real person these days with me. The usual dramatic standbys of adultery, alcoholism, sexual secrets, cruelty to children etc. just don’t do it. And people kept on listening, ‘absorbed’, even though there was next to no plot. You can keep a piece like that moving along through a springy rhythm, some variety of voices and scenes. When I listened, after a gap since the recording in July, I wasn’t always sure what the next scene was; a good sign. And the play, as another pal indicated, is much more about the girl receptionist at the hotel where Samuel Beckett stayed (incognito) than about the writer himself. Another said, ‘Well you’re there in all three main characters: as the ambitious student, as the teacher and as the ‘wise’ older writer, Beckett,’ which I found faintly worrying. I know I’m wrapped up in myself, but thought I was creating characters. This perceptive pal (a former TV producer) liked the fact that stuff (or not too much) wasn’t spelt out, that he had to join up the dots. The pressure is almost inevitably for you to up the ante these days. Which I mainly resist, being old in the tooth and set in my ways. ‘He never gives you the big scene head on,’ the producer of the TV film ‘Angel Voices’ once said, getting me to heighten the confrontation near the end between the Head Chorister and the Choirmaster (she was right to do so in that instance). I don’t really do ding dong is what it amounts to, for better or worse. I like the way Henry James in ‘Portrait of a Lady’ cuts away from Isabel’s discovery of the horror of her marriage, not taking the obvious more direct approach. It was a book I used to love, and I think influenced me. And Jane Austen didn’t bother, either….‘let other pens dwell on guilt and misery.’

And even with essays like this I only seem to get going tangentially - Giles Fraser and we’re off. I started an essay about a month ago with a definite subject, about film-going (with a note of my enchanted Chesterfield childhood thrown in, and a bit about my mum, who gets shorter shrift in these essays than she merits. She loved the pictures, kicking off something in me. So let’s give her and the flicks a go. The piece started like this:

On my way to and from school when I was a little kid was a little enclave – I don’t know the word for it – backwater? - a cobbler’s in a sizeable wooden hut (I can still smell its interior) at its entrance, a blacksmith’s a bit further in, where we would stop to watch horses being shod. Beyond, along what wasn’t a properly made up road, were little Victorian cottages with pretty rockery style gardens immediately outside their front doors. This little street – track - was immediately adjacent to a railway line in a deep cutting behind a high smoke blackened wall. (This whole area was razed in the Seventies to make way for Chesterfield’s ring road). With other kids I used to clamber this wall and walk along it. There was a drop the other side that would have killed you, which was why we did it, of course. One morning our Junior School Headmistress, Miss Jones, a formidable woman, announced at school assembly: ‘It has been reported to me..’ demanding those who had been walking this walk to come to the front. I was the only one to do so (the honourable schoolboy?), shamefaced, blushing. Not a bad tactic, actually. I finally received a form of praise: ‘Well, Stephen has been the only honest boy..’ But what I remember about that long gone enclave, most of all, are the cinema posters – quite modest in size – on display at its entrance opposite the cobbler’s, and which I viewed daily coming back and fro from school. ‘The Man with the Golden Arm,’ I remember in particular. I didn’t know what a golden arm was, though it didn’t sound very pleasant – and the film was certificated beyond my, then, six years. I still remember Frank Sinatra as one of the actors (I’d thought him just a singer). There were other faces on the poster, a little line of its stars, which meant it would have been the first time I noticed Kim Novak.

I now know that a year or so later she was in ‘Pal Joey,’ (another film I saw a poster for). This is because I looked her up last night, half way through one of my regular viewings of the film by which she is best remembered – ‘Vertigo.’ This masterpiece barely makes sense on plot level: it’s ‘tosh’ – as a friend said to me back in the Eighties. I’d taken her to it; the film had just surfaced having been next to unavailable (there were occasional bootleg reported late night showings). Back in circulation with specially cleaned up print after near thirty years since I’d first seen it with my mum (I was 10) I took the first opportunity to re-visit the film (certain images of which I retained) at a matinee one West London mid-week afternoon. I wasn’t the only one eager to see it. The playwright Christopher Hampton was sitting behind me. I swooned through it all over again – it’s a kind of rhapsody of romantic longing with a thriller plot- and went back to see it with my (‘it’s tosh’) friend the following day. The plot is tosh, but it’s not the (bizarre) plot that carries it, but its atmosphere…

Now the problem with that - so far as these essays go - was it was a bit worked up. Something else - a different form of writing – is going on there. What I had intended to do with what would have been the thirteenth essay (I was aiming for fourteen, like the tracks on a Beatles’ LP) was then ramble a bit about movies I’d seen from ‘The Greatest Show on Earth,’ the first I remember. It has a rail crash which gave a five year old nightmares; there’s what I recall as a blue flash and then the circus animals escape from the trucks. That would have led me to certain images from ‘Vertigo’ which never left me during that thirty year gap. Impossible to imagine, these days, a film disappearing for so long. When I went to San Francisco, where the film is set, I did a ‘Vertigo’ tour of its locations, a bit nutty, working it out for myself (there are now official tours). I discovered that in the church where Jimmy Stewart follows Kim Novak out into the graveyard in that early hypnotic chase sequence, in reality the door leads into a closed vestry. Hitchcock puts a filter on the film for the subsequent near silent, ravishingly beautiful graveyard sequence (just the clicking of footsteps) where Novak visits her ‘predecessor’ Carlotta Valdes’ grave. Novak’s is a terrific performance, in a very tricky role and I would later have noted that, many years later, 2012, I think, I would meet an actor at a BBC reception I didn’t recognise at first - a benign and still handsome old man who introduced himself to me (we were early) and got chatting. He was Richard Johnson, who it turns out (I learnt it only last month looking up Novak) was once Kim’s husband. So there we are – one handshake away from an actress who once appeared so impossibly distant (even more unattainable that the 19 year old Sue Limb). It was Novak in receipt of that famous line from Hitchcock (he had wanted someone else for the role); seeking ‘motivation’ for her twin characters, she was told, ‘It’s only a film Miss Novak.’

Mum and I used to talk about the films as we headed back from town home down Hollis Lane. My dad’s regime of shifts meant he would be in bed or at work and I remember only once going with him to the pics. Another Hitchcock: the great ‘North by North West’. We waited in the foyer before the film for the manager to come down, who then let us in for free: my dad being the town’s police inspector (some small town trade off). After the breathless ‘NBNW’ (which I once recorded on an audio tape recorder from the television in the days before VHS – or readily available scripts - to see how it worked) we went for plaice, chips and peas in the cinema’s restaurant, with bread and butter (maybe margarine?) and a pot of tea. They were the happiest three/four hours of my life: it was 1959, I was 12…..

Which is all right if verging on the lyrical, but a bit too formally autobiographical (the writer’s early life), threading past and present; that was then and this is how far we have come. I know what I’m doing, though – and I like a few more surprises, both in playwriting and essays. ‘Where is this taking me?’/ ‘Oh, that’s what it’s about.’ And ‘lyrical’ accounts of other people’s childhood bore me (even Tolstoy’s). As my old History teacher said, having recently read the previous dozen essays: ‘Come on, you’re a little boy from Piccadilly Road (see Piccadilly) who’s moved in all sorts of exalted circles and met a remarkable range of people in so many different situations. Twist it into a long story aka a novel.’ He’s regarded these essays for some time as a dry run at a longer form of fiction. He also, incidentally, bemoans my emphasis on gay promiscuity: ‘You’ve been there long enough.’ I’m also amused at the way he hints a preference for my earlier more succinct style of essay writing (‘like your essay for me about the coming of the railways in the 19th century’).

In short, as Mr. Bennet once advised his modestly talented third daughter, who had spent too long at the piano: ‘Thank you, Mary. You have entertained us long enough.’ It’s possible I’ll get Proustian and autobiographical in a different format (though doubt it): the smell of urine and disinfectant in public lavatories, perhaps, summoning up a host – a haze - of fond memories. I neglected to say when I did describe cottaging in an earlier essay that, just after I arrived in London, I met the great (late) director Bill Gaskell who was in conversation with another distinguished director (still extant). They were regretting the closing of some well-known London pissoirs. Fresh faced me (it now makes me laugh) was a bit surprised and disappointed. I’d expected them to be discussing Harley Granville Barker or Osborne.

I’ve wanted to describe, under various ‘topics’ - as the mood or inclination takes me – how I’ve felt this summer, having moved into what’s surely my last house. There’s a crochettiness has kept coming through. But it’s the way I am – increasingly like some eccentric who’s moved into Richmal Crompton’s William Brown’s village. If William was listening outside my door the other night he would have heard me yelling out ‘like!’ every time a young woman on the radio kept littering her sentences: ‘like…like…like.’ William, implausibly innocent of sex, probably wouldn’t register an embarrassing eroticism that keeps surfacing in a number of the essays. But I cheer myself with the journals of John Cheever, another elderly gent, and his (cheerfully depressive) musings: ‘I may fall in love with a lonely grocery boy. A gentle heart and a capricious cock.’ Update that for Deliveroo with me. And I don’t forget how the great John Maynard Keynes (they didn’t teach me this in economics at school) once looked lasciviously down from high table in Cambridge, at the - male - undergraduates with intentions that would have had him arrested then or now.

I’ve been much taken with the film ‘God’s Own Country’ lately (which has quite a bit of the man on man I like - and features cottaging). I saw it three times in two weeks - not for the cottaging: it’s a masterpiece. Josh O’Connor, who plays the lead, is drunkenly despairing in the opening sequences of the film, though breaks out of his emotional numbness by the end. It’s an astonishing performance in which he also runs a dialogue scene completely bollock naked (worth the price of a couple of cinema tickets). A friend, who’s known me for forty years, after hearing of my triple trip to the cinema, wondered why: ‘I’ve never seen a film three times.’ I had to come clean and texted saying that the buried emotion and need in the film struck a chord with me. ‘It’s the buried theme in most of your web essays,’ he replied. Another friend, who’s known me since school, had said previously, in relation to Father’s Day (which had moved him): ‘Well losing your father when you did must have had its effect, as well as making you more resilient.’ I’ve always assumed that, on the whole, my emotional sights are set pretty low. But this form of writing is, surprisingly, just like a play in which people come to conclusions, judge, discriminate. And, as with a play – sometimes years after the event - you learn something about yourself. Analysts (I believe) encourage their patients in a stream of consciousness, where the true subject – the problem, knot or inhibition - eventually bubbles up. I’ve tidied and smoothed the odd transition after writing, but these pieces have been pretty free flowing, crustiness and all; a lot angrier about society’s treatment of homosexuality than I imagined, and quite possibly revealing more yearning for intimacy/affection than I normally credit myself with. There’s a lot of ‘if only’ about them. Well, it’s a bit too late in the day for the full (Love Island) number. And all my parts, sadly, aren’t in - how shall I put it? - Josh O’Connor order. I’m not very keen, as I say in the introduction to a sidelined novel, with what often blows in with love. Possessiveness. Jealousy. When last infatuated I finished up punching the loved one. But I also remember the feeling at that time of also being in love with the whole world.

So there it is: ‘if only.’ You wonder if you’ve missed the point of life – though just when I was feeling a bit maudlin about not loving enough I read that there’s a new movement called ‘sologamy’- mainly women who go through public ceremonies marrying themselves. This is a very encouraging development, though notice that the girls go to the expense of buying wedding dresses and rings. I think I had my own secret (cheap as muck) ceremony quite a few years ago now. Made my bed, lay on it. Eric James, my priest friend, with whom I’d talk of these things, said – he was also talking about himself – ‘Well, you’ve made more of your friends as a result.’ I texted one of those friends over the weekend, a racing pal, an ex-student of mine, having done the rounds of the major race meetings by bike this autumn and currently living in a tent close to Chantilly racecourse,. I was once pretty sold on this handsome fellow – who sadly hasn’t a gay bone in his body. (When he told his mother I was gay she said, ‘I know.’ ‘How do you know?’ ‘He said he admired my curtains.’)

Well, John got married (young). The marriage went wrong and he was very unhappy for a time. ‘You know how to live on your own, Steve,’ he said. ‘You like it. I don‘t.’ I’m not sure I always do but have got used to it, though there are the usual anxieties about increasing frailty. I mentioned to him lately about this desire of mine to maybe give up, live a little more, change my life a bit, work less - be more ‘receptive to experience’ as another priest pal suggests. John, somewhere in France (a Latinist, ‘Gaul’ he likes to call it) replied by reminding me that his dad had died six weeks after retiring, aged 70, on his first proper holiday in Blackpool. And I must say, honestly, I fancy my friend’s heroic autumn journey (Leopardstown via Newmarket, Doncaster and Chantilly), more than finding someone to step into the sunset with….but I couldn’t do the hills: I’ve got lately to thinking about an electric bike. Oh, dear. As Natasha Kinski bemoaned, with her best Polish accent, in ‘Tess of the D’Urbervilles’: ‘It’s too la-yte, Angel. It’s too la-yte.’

I started these latest essays in April (before the 2000 Guineas – see Pass It On) and it’s now the weekend of the Arc de Triomphe, still just about sunny and warm. John, in Gaul, with ground sheet presumably, is hoping for good ground for his 16-1 fancy. But there was a shower of rain this morning, the heating is beginning to creak on in the house I’ve lately settled into. A bit of fiction’s got abandoned this summer, a play was recorded, these essays – herewith - brought to a close (with thirteen tracks - though this last one’s a bit of a double number). I’ve found the freewheeling essay form satisfying and want to get some of its breeziness- rapid, light brushstrokes/going forwards, back, sideways at will - into my fiction writing, if I can, without losing the traditional virtues of the novel: an engaging narrative, fully rounded characters. John Lennon told George Martin that he wanted ’Strawberry Fields’ to be both ‘fast and slow at the same time.’ I could do with a resident George.

The last Beatles’ LP – also ending with a bumper compilation of bits and bobs - tailed off with Paul at his most upbeat: ‘And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.’ I don’t think I can manage to live up to that injunction (and the Beatles at that time, I note, were at daggers drawn) so will settle for a line I picked up from somewhere – a newspaper article, if memory serves, some Christian commentator, probably - about God’s assurance that our ludicrous inability to be who we want to be is ultimately forgiveable and forgiven. ‘Was he a disappointed man?’ the novel I was writing begins. ‘Or just getting old?’ Just getting old, I think. (October 2017)