Joe

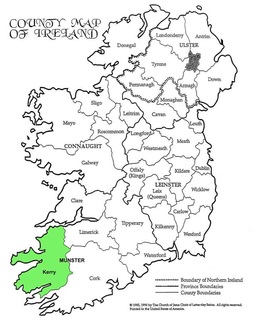

Is not his real name. We met behind a tree in Turnham Green in 1984, one o’clock, a misty November early morning. I had a glimpse of someone just leaving him as I approached. And there he was, in that late night pick-up spot, up against a tree, maybe – I don’t remember - inviting me with a gesture to join him. I was part drunk, with a dinner jacket under my raincoat, having come from a House of Commons dinner. Part drunk, but I knew what I liked and after a few minutes I said, ‘Do you want to come back?’ It was a night that turned tender. He later said that he thought I was a schoolboy, seeing and misunderstanding the DJ under my mac. I had a boyish face, then – I was 37, he ten years younger, stocky, built like a boxer, and Irish. We exchanged names the following morning, he laughing at the Irishness of his. I gave him my phone number: he was a great kisser.

A month elapsed, and then – just after Christmas – an Irish voice said down the phone: ‘Remember me?’ I went to pick him up from a snooker hall in West London (I am being careful with the geography for reasons that will become clear) and a relationship developed. The same pattern: a gap, then a late night phone call. I got the car out or paid for a taxi. The unpredictability of his appearances added to the excitement. He had no apparent job, worked occasionally on building sites or market stalls, existed on disability benefits while playing football and swimming. In short, was the kind of bloke Mrs. Thatcher thoroughly disapproved of. I was the ambitious – ‘driven’ – playwright with a swish flat, entranced by him. I couldn’t ring him. He seemed to live in a variety of places, rooming houses, sometimes with a sister. He admired what I did, my life. He drank too much, he knew, smoked too much. I used to love the smell of the big spare bedroom with the double bed after he had gone – boozy and warm. My life would resume its normal well-ordered pattern for a time – and then the irruption. What we had fell short of love but was more than ‘mere’ sex (no offence to mere sex). No one but his partners – I assumed there were occasional others - knew he was gay. It was a problem with him. He hated queer, ‘campy’ behaviour. He was bright, had a lot of humour, read Kurt Vonnegut, whom I have never got through, and when he entered my flat, and the study door was open, its book shelves on display, would say, ‘The Library is open.’

After about two or three years – 1987 – there was a considerable gap. I thought he had disappeared, wondered if he had gone to prison: benefit fraud? He wasn’t averse to picking up (how?) a stray credit card and using it, and once arrived on a bike with about fifty gears, which I never saw again. There had been an incident (he had told me) with a plank late one night, when he had gone for somebody, and on our only attempt at doing something normal, like going out together, he had got into an argument with the club’s doorman, meaning we weren’t admitted. What he did during the day I was never privy to. He would arrive after ‘Newsnight’, stay till morning (often the best time), have a cup of tea and go. He once hung round till mid-morning as I worked but eventually wandered into the study to say he was off. The pubs were opening, presumably. He had friends, and referred to them, but was insistent I should never acknowledge him in the unlikely event of our being in the same pub at the same time. But I annoyed him, also, by going off to sleep in my own bed for most of the night – he was a restless sleeper – before creeping back in first thing in the morning.

After about six months, that late Spring and early Summer of 1987, I went looking for him, a tour that took me to a Polish rooming house he had once pointed out, run by some kind sad faced women, who showed me the room he used – cavernous, looking out on incessant traffic, plaster peeling from the ceiling: ‘Only he hasn’t been here for a long time.’ They directed me to the local market. ‘A lot of people don’t use their real names here,’ a stall holder told me. At the snooker hall I left a message with the owner: ‘Tell him Steve called. I’m a writer. He was helping me with a play I’m doing about snooker’ - which was not far from the truth. I finished up in a particular pub he had mentioned. It was Saturday late morning and very quiet, and there was his name on the walls in gold letters, the winner of a pool competition. I left a note in a sealed envelope with the barman and offered the same kind of (pretentious) explanation. The barman stuck the letter behind the bar.

In July, a Saturday afternoon a month or so later - it was Election year - the phone rang. I was talking to a neighbour on the stairs outside my flat and had – just - a feeling it would be Joe. My downstairs neighbour and me never resumed our conversation, that afternoon, though she – in an unsatisfactory but long lasting adulterous relationship with a Parliamentary journalist – readily understood. Joe sounded impressed by my tour (‘You’ve been looking for me’) rather than annoyed – even flattered. ‘Haven’t you got anybody better than me?’ he would sometimes say when we met after a gap. There were others, and I was generally honest. I fell in love at that time with a young would-be actor, part French, part Crouch End, straight, sadly, though I slept with him. ‘Stick to Joe,’ he told me, understanding me better than I did myself. I have never wanted to give myself completely to another, and never wanted another to do the same. It was, also, the busiest time of my life – I moved from play to play – some of them demanding. I was leading (seemingly having stumbled into it) a glamorous life – among actors, writers, journalists, politicians. I was openly gay (as they say), though with a sex life largely confined to Joe’s timetable: about six times a year between twelve and one in the morning, and with a reprise about eight the following morning. I would have seen him much – much - more, but when I tried to pin him down (‘What about this Saturday?’) he would say, ‘Definitely, Steve,’ and clear off again for six weeks. ‘Definitely/maybe’ as the song says. Looking back, I think I was keener on him than he on me. What it probably came down to was the worryingly lethal question he once asked me before falling asleep: ‘Why can’t you love me, Steve?’ Because it wouldn’t have worked. Finally – brutally – he was feckless and I wasn’t. ‘There’s a wall around you, Steve,’ he’d say. He was right, I’d got him in a convenient compartment.

Once I visited him – a hot summer morning in the back bedroom of a little house among many identical little houses on a long terraced street, where he was living with an old guy, who liked a bit of company. The old guy was Eastern European, and Joe called him Dubjeck. He was away. If I look back at a couple of hours of sheer sexual happiness it was that August morning on top of the sheets. I probably knew then that, whatever happened for the rest of my life, I would be always able to say, ‘I’ve had my moments.’

We are approaching the 90s, and there was a girlfriend mentioned. ‘She can handle my drinking, Steve.’ And then a call on a Sunday afternoon to a pub in Kensington – not one of his usual haunts - where this secretive man held my hand in full view on the pub table while telling me that it was serious, that he had moved in with her. I think he quite enjoyed the drama of it, but the implication was that we’d come to an end. I bought him a drink and left. That was it, and I was upset, though glad for him. He needed some kind of stability. A week or two later he was on the line again. ‘I thought we’d finished,’ I said. But he wanted sex – or homosexual sex – and she, he told me, seemed to accept that it was OK for him to spend the night elsewhere with his mates. I had vain hopes of a kind of future but didn’t question much. These were the last throws of the dice. I probably ‘saw’ him a couple of times after that. He’d become recriminatory: ‘You don’t love me, Steve,’ as if that was the pre-requisite for our couplings. And yet, there he was: handsome, potato-faced, here for the night. The implication was that she loved him. I hope she did. They had a baby. I know because he rang me from the hospital the early morning of its birth. I like the idea of a new father ringing his ex-boy friend to announce the birth of a son. And the arrangement between us fizzled out (I describe its last splutter in the previous essay). In an era of mobile phones and e mail we might still be in touch. But it’s probably as well we aren’t: he was terrified of his girlfriend finding out, of anything jeopardising that relationship. A friend of mine once said, ‘You’ve always made a lot out of a little, Steve.’ Maybe. It wasn’t one of the great love affairs of the century. But I look back on Joe and those ten years as one of the best things of my life. His son will be over twenty by now, and if he is gay, ‘no problem’ as they say – and, as I write this, I realise this is a tale of a transitional era.

A month elapsed, and then – just after Christmas – an Irish voice said down the phone: ‘Remember me?’ I went to pick him up from a snooker hall in West London (I am being careful with the geography for reasons that will become clear) and a relationship developed. The same pattern: a gap, then a late night phone call. I got the car out or paid for a taxi. The unpredictability of his appearances added to the excitement. He had no apparent job, worked occasionally on building sites or market stalls, existed on disability benefits while playing football and swimming. In short, was the kind of bloke Mrs. Thatcher thoroughly disapproved of. I was the ambitious – ‘driven’ – playwright with a swish flat, entranced by him. I couldn’t ring him. He seemed to live in a variety of places, rooming houses, sometimes with a sister. He admired what I did, my life. He drank too much, he knew, smoked too much. I used to love the smell of the big spare bedroom with the double bed after he had gone – boozy and warm. My life would resume its normal well-ordered pattern for a time – and then the irruption. What we had fell short of love but was more than ‘mere’ sex (no offence to mere sex). No one but his partners – I assumed there were occasional others - knew he was gay. It was a problem with him. He hated queer, ‘campy’ behaviour. He was bright, had a lot of humour, read Kurt Vonnegut, whom I have never got through, and when he entered my flat, and the study door was open, its book shelves on display, would say, ‘The Library is open.’

After about two or three years – 1987 – there was a considerable gap. I thought he had disappeared, wondered if he had gone to prison: benefit fraud? He wasn’t averse to picking up (how?) a stray credit card and using it, and once arrived on a bike with about fifty gears, which I never saw again. There had been an incident (he had told me) with a plank late one night, when he had gone for somebody, and on our only attempt at doing something normal, like going out together, he had got into an argument with the club’s doorman, meaning we weren’t admitted. What he did during the day I was never privy to. He would arrive after ‘Newsnight’, stay till morning (often the best time), have a cup of tea and go. He once hung round till mid-morning as I worked but eventually wandered into the study to say he was off. The pubs were opening, presumably. He had friends, and referred to them, but was insistent I should never acknowledge him in the unlikely event of our being in the same pub at the same time. But I annoyed him, also, by going off to sleep in my own bed for most of the night – he was a restless sleeper – before creeping back in first thing in the morning.

After about six months, that late Spring and early Summer of 1987, I went looking for him, a tour that took me to a Polish rooming house he had once pointed out, run by some kind sad faced women, who showed me the room he used – cavernous, looking out on incessant traffic, plaster peeling from the ceiling: ‘Only he hasn’t been here for a long time.’ They directed me to the local market. ‘A lot of people don’t use their real names here,’ a stall holder told me. At the snooker hall I left a message with the owner: ‘Tell him Steve called. I’m a writer. He was helping me with a play I’m doing about snooker’ - which was not far from the truth. I finished up in a particular pub he had mentioned. It was Saturday late morning and very quiet, and there was his name on the walls in gold letters, the winner of a pool competition. I left a note in a sealed envelope with the barman and offered the same kind of (pretentious) explanation. The barman stuck the letter behind the bar.

In July, a Saturday afternoon a month or so later - it was Election year - the phone rang. I was talking to a neighbour on the stairs outside my flat and had – just - a feeling it would be Joe. My downstairs neighbour and me never resumed our conversation, that afternoon, though she – in an unsatisfactory but long lasting adulterous relationship with a Parliamentary journalist – readily understood. Joe sounded impressed by my tour (‘You’ve been looking for me’) rather than annoyed – even flattered. ‘Haven’t you got anybody better than me?’ he would sometimes say when we met after a gap. There were others, and I was generally honest. I fell in love at that time with a young would-be actor, part French, part Crouch End, straight, sadly, though I slept with him. ‘Stick to Joe,’ he told me, understanding me better than I did myself. I have never wanted to give myself completely to another, and never wanted another to do the same. It was, also, the busiest time of my life – I moved from play to play – some of them demanding. I was leading (seemingly having stumbled into it) a glamorous life – among actors, writers, journalists, politicians. I was openly gay (as they say), though with a sex life largely confined to Joe’s timetable: about six times a year between twelve and one in the morning, and with a reprise about eight the following morning. I would have seen him much – much - more, but when I tried to pin him down (‘What about this Saturday?’) he would say, ‘Definitely, Steve,’ and clear off again for six weeks. ‘Definitely/maybe’ as the song says. Looking back, I think I was keener on him than he on me. What it probably came down to was the worryingly lethal question he once asked me before falling asleep: ‘Why can’t you love me, Steve?’ Because it wouldn’t have worked. Finally – brutally – he was feckless and I wasn’t. ‘There’s a wall around you, Steve,’ he’d say. He was right, I’d got him in a convenient compartment.

Once I visited him – a hot summer morning in the back bedroom of a little house among many identical little houses on a long terraced street, where he was living with an old guy, who liked a bit of company. The old guy was Eastern European, and Joe called him Dubjeck. He was away. If I look back at a couple of hours of sheer sexual happiness it was that August morning on top of the sheets. I probably knew then that, whatever happened for the rest of my life, I would be always able to say, ‘I’ve had my moments.’

We are approaching the 90s, and there was a girlfriend mentioned. ‘She can handle my drinking, Steve.’ And then a call on a Sunday afternoon to a pub in Kensington – not one of his usual haunts - where this secretive man held my hand in full view on the pub table while telling me that it was serious, that he had moved in with her. I think he quite enjoyed the drama of it, but the implication was that we’d come to an end. I bought him a drink and left. That was it, and I was upset, though glad for him. He needed some kind of stability. A week or two later he was on the line again. ‘I thought we’d finished,’ I said. But he wanted sex – or homosexual sex – and she, he told me, seemed to accept that it was OK for him to spend the night elsewhere with his mates. I had vain hopes of a kind of future but didn’t question much. These were the last throws of the dice. I probably ‘saw’ him a couple of times after that. He’d become recriminatory: ‘You don’t love me, Steve,’ as if that was the pre-requisite for our couplings. And yet, there he was: handsome, potato-faced, here for the night. The implication was that she loved him. I hope she did. They had a baby. I know because he rang me from the hospital the early morning of its birth. I like the idea of a new father ringing his ex-boy friend to announce the birth of a son. And the arrangement between us fizzled out (I describe its last splutter in the previous essay). In an era of mobile phones and e mail we might still be in touch. But it’s probably as well we aren’t: he was terrified of his girlfriend finding out, of anything jeopardising that relationship. A friend of mine once said, ‘You’ve always made a lot out of a little, Steve.’ Maybe. It wasn’t one of the great love affairs of the century. But I look back on Joe and those ten years as one of the best things of my life. His son will be over twenty by now, and if he is gay, ‘no problem’ as they say – and, as I write this, I realise this is a tale of a transitional era.