Almost famous

People ask you sometimes, on learning you’re a writer, ‘Are you famous?’ I tend to say, ‘Almost famous,’ which was perhaps true at a couple of times in my career. But, without trying, I’ve met many people who are famous – I don’t mean just actors and writers (in my public profession), but also in journalism and politics – and am generally without envy. I seem to have an aptitude for meeting a number of these people on the cusp of their fame, just before they hit critical mass - Neil Kinnock, when he was a backbench MP (though clearly going places); Evan Davis in his early days as a BBC economics correspondent (number 3 on the team? definitely the junior) and, in my own field – and therefore most tricky - the writer Hanif Kureishi during his more dogged days before ‘My Beautiful Laundrette.’ Later I would meet and ‘tutor’ a raft of brilliant young writers at the National Theatre, but these were laid on for me by the Literary Manager at the time – they were not accidental meetings and I don’t include them, though still see (or am in touch with) one or two. A fair proportion of them, even then, I could see were more able than me, and have hit fame subsequently - despite my help, as I like to say

Let’s deal with the difficult one. I came across Hanif for the first time - to speak to - at a summer party of our then agent, Sheila Lemon. I’d seen him before - across the upstairs foyer at a Christmas drinks do at the Royal Court theatre my first week in London. He had had a play running there – he was pointed out. I remember not liking the look of him much but I can’t remember why. It’s maybe because he was in the company of Max Stafford-Clark, the director of his play and Royal Court boss, with whom I had not hit it off: I had been appointed Young Writers’ Tutor in Max’s absence. Max objected to that. My predecessor in the job had been the great Caryl Churchill, but I don’t think it his objection had anything to do with me in particular – I was up and coming - but the fact that he’d not been consulted. (I’m pleased to say I held the job for four years, and was asked to stay on even then.) Hanif would take over from me. We crossed paths at that earlier time, too. Danny Boyle was a young director at the Court, who’d chosen, as his first production there, what I still describe as a ‘Polish Pantomime’ to direct. Danny had liked a stage play of mine and asked me to write a version of the Polish play, a subversive piece. We would travel to Poland which was still Communist, talk to the original cast and director, in a hush hush way. But I had a – very - good job in the offing at the BBC and couldn’t make much of the Polish play’s surreality. I turned it down (‘Good career move,’ someone said, later, when Danny was a film director). Danny had come up to Oxford where I was then living – the persuasive operator in him at work even then – to get me to change my mind. But I was adamant. Hanif took on the job. I remember Danny being surprised I drove a MG Midget, as I took him back to Oxford station. From my stage work he’d seen me as a gritty Northerner.

And then, 1982, there was Hanif on his own at Sheila’s party, handsome, funny. We got on, delighted in each other’s company, exchanged phone numbers etc. Hanif’s habit was to ring, generally late evening, and without introducing himself, would say something like, ‘I piss on your grandmother’s vulva.’ There may have been a reason for this approach that had to do with Arab curses, but I’ve forgotten.

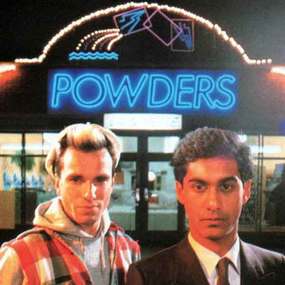

Hanif was the kind of guy you had come to London to meet. He once said to me that not a single day of his life had gone by without someone referring to his race: he is, in fact, the son of a Pakistani father and an English mother. I met his dad once at the Hampstead Theatre where Hanif had a play, ‘Birds of a Feather’ and the old guy, who was a would-be writer himself, was thrilled for his son. Picked out – isolated - at school and elsewhere Hanif may have been, but his colour and background was the making of him as a writer (as well a certain ability, of course). Salman Rushdie had just had an enormous success with ‘Midnight’s Children’. The door was off its hinges and battered in for what at one time were called Commonwealth Writers. I was writing a lot of film for television then, and came across Hanif one summer or autumn evening – we were cycling on the towpath between Putney and Hammersmith. Hanif had seen one of my films the night before, an adaptation for Granada called ‘Miss A and Miss M.’ ‘I want to write films like that,’ he said. And had, it turned out, the vision to write films better than that. He had been commissioned by Channel 4 to write about young Asians in England, the film that became ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’, knew he was on a winner, thought it was more than a television piece, wanted a different director, stuck the script through Stephen Frears’ door, and an Oscar nomination was the eventual result. He had done all this without taking the advice of Sheila, our agent, who had urged caution (Hanif never really forgave her). I would never have had that assurance. We once had a meal - Hanif, Sheila and I – Hanif wanted me to be there because their relationship was still edgy, and he burst out at one point, his remark aimed directly at me: ‘You’ll never be very successful because you’re too nice.’ Extraordinary: it must have emerged from something I said. I don’t think I’m that nice (my closest friend certainly doesn’t think so). But I am ambivalent about success and the remark probably says more about Hanif’s approach and attitudes than about mine. Sheila would ring me every now and again, after that meal (we took her out jointly: she was touched), knowing we were pals, to ask how he was; was frank that she didn’t know how to handle him - and I learnt my place in the pecking order of her clients. Later he left her and encouraged me to do so. But I was happy for many years with Sheila. She had brought me on as a young writer. What I knew, not brilliant like Hanif, was I needed her more than he did.

I would meet him from time to time at the Dove, on the towpath near Hammersmith Bridge – he lived in Baron’s Court, me in Chiswick. Our bikes would be parked together on the railings: his more stylish than mine. They were the happiest times. Though I had fed him and introduced him to people, including the Kinnocks (whom he was keen to meet – Neil was Labour Leader then) there was never any repricocity. ‘Oh, you ought to meet Michael Hastings,’ (say) never led to any meeting. But we were thick. It felt like a love affair. When he was asked to tutor for the Arvon Foundation, the organisation set up by Ted Hughes offering a week’s residential course for young or inexperienced writers, Hanif asked me to accompany him as tutor. I wouldn’t have been asked otherwise, though the director of the Arvon at Lumb Bank is now my current radio producer, David Hunter. It was a near disastrous week in glorious weather - May, I think. I drove up to Yorkshire with Hanif, who couldn’t drive then, as passenger, he telling me to keep my hands on the steering as I pointed out places in South Yorkshire where I had taught. Of the fourteen or so students, about eight were from a black women’s collective in South London, attracted by Hanif as tutor. They all knew one another - too well, They were dour, which puts it cheerfully. There were disputes. They all seemed to be writing about Sickle Cell Anaemia. I was the diplomat in a way that, even less nice these days than then, I wouldn’t be now: this group was bitter and irreconcilable. There was some god almighty rumpus on the last night and we tutors left them to it on the basis of who were we to prevent them having a good scrap? The two of us (I’d say young-ish white males - though Hanif doesn’t qualify for one of the adjectives, and which perhaps proves his remark about ‘Not a day goes by…’) had a great time away from the fractious group, including at one point a visit to Sylvia Plath’s – defaced – grave among an overgrown graveyard. Later we had a card from David Hunter and his partner Moura, the organisers, commiserating and resolving never to allow an already existing group in such numbers as students. We went again a year or two later to tutor a much more tractable – and talented – group, and glimpsed Ted Hughes – who slipped in and out at the end of the bar/dining room, like a shadow.

Hanif had had his huge success with ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’ by then. I was doing pretty well in television and didn’t envy him: I regarded him as the ‘better’ writer, more confident and daring than me. This led to disasters, of course. His second film with Frears, ‘Sammie and Rosie get Laid,’ originally called ‘The Fuck,’ was charmless. He had asked me to bring Kinnock along to the preview, and just before the (split screen) ‘dirty bits’ Hanif nudged me in anticipation. Multiple copulations followed and on my other side Kinnock (who was with Glenys) whispered ‘We’re not used to this.’ The post screening dinner was glum. I had a chat with Frears who said, ‘I’d no idea what I was doing through most of it or what it was about.’ Sheila (with her husband) looked like thunder, though her marriage had turned rocky (‘Imagine an evening at their house’, Hanif said) and Salman Rushdie (pre-Fatwah) turned up.

Hanif’s own love life was complicated. When I brought him back down from Yorkshire after our second Arvon stint he said to me as we hit West London, ‘I want to come home with you.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, she’s there.’ ‘She’ being the woman he would soon marry. He had encountered many problems with his family over the world he portrayed in ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’ and was feeling isolated: ‘You have great friends. Mine are deadbeats.’ He was probably doing too many drugs, and, I remember, wanted us to spend a weekend on LSD together, wandering round Chiswick House and grounds or somesuch. But ‘the Nervous Nelly,’ as he called me, balked at that. I realised that I was performing the role of elder – wiser, more stable – brother, and wasn’t entirely comfortable with what we might now call the Jamie Murray role. One Saturday night he asked me round to his place. He sounded low and I bubbled away for about three quarters of an hour in his company before he told me his dad had died that week. He had put me in a false position. I couldn’t say it at the time because he was grieving but was quietly angry with him for not making his misery clear from the start. It was bizarre behaviour: I thought he simply needed cheering out of a ‘mood’. Later, writing a fine book about his father, he excluded me from the narrative, saying that the aftermath of his father’s death had been spent in isolation. It wasn’t. I was edited out.

But after years of ‘success’ things were not going so well for me. He wrote, or completed, his first novel ‘The Buddha of Suburbia’ and sent it me the manuscript up North where I was then staying. I didn’t like it much – found it cartoony, two dimensional – and wrote to tell him so. I said I thought he had missed a big opportunity to write the greatest novel about the theatre since ‘Nicholas Nickelby,’ completely failing to notice that ‘Buddha’ was ground breaking in its portrayal of British Asians. It made a good television series, but I think by then I felt that Hanif was having too much success on my territory, television (i.e. I was wasn’t). The worm had entered the bud.

He wanted me to dramatise a political short story of his, but I found the language of the story – ‘olympian’ or ‘neutral’ (like a translation ) and its premise unlikely - and told him so. My justification for this is he was savage with others’ writing. So an offer became a hurt. We were due to write a sketch together at a Royal Court fund raiser, but he was very late for our meeting and I went a bike ride by the river instead. He was critical of Kinnock during this period leading up to the 1992 General Election. It was easy to be so, but he went to print in the ‘New Statesman’ with a lead article about Neil’s failings. I had introduced them; Hanif had become one of his celebrity supporters. Kinnock phoned me: ‘You tell your friend, Hanif Kureishi, that (expletive deleted) rat etc.’ And mistakenly I did. I did, at least, wait till Hanif rang me. And tore him off a strip – what was the point of an article like that a couple of months short of an election? He was first silent, then evasive, and – I realised later – lied a bit. I’m not bothered (after near twenty five years) about the details of the row, but it was the end of the friendship. The Headmaster, so to speak, had got the Head Boy to do his dirty work for him and the (too obedient) Head Boy should never have complied.

I went a long wander in the Nineties, disillusioned with myself and my work. I know Hanif asked after me and I congratulated him on his answer machine when his twins were born. There was no reply to that – he didn’t take the (intended) opportunity to make up. His marriage later foundered, and Hanif wrote a brilliantly cruel novel ‘Intimacy’ about that break up. It verges but just avoids on the self pitying, and will outlast him. I wrote a postcard to him about that. No reply. His work subsequently has been patchy – but he allows himself the freedom to fail – and I find the films lack urgency, but I e-mailed him a couple of years ago to congratulate him on his CBE, and got a pleasant reply. There have been one or two more splutters of communication, including one on speculation about Stephen Kinnock’s sexuality (‘Are you responsible for this?’). I miss his humour – which isn’t on much display any more in his public pronouncements where - always with a slightly whiny voice - he appears lofty, even grandiose. That wasn’t his manner in those brilliant years of the Eighties, when I was nearly famous and he became famous - and I’m glad to have known him then.

Let’s deal with the difficult one. I came across Hanif for the first time - to speak to - at a summer party of our then agent, Sheila Lemon. I’d seen him before - across the upstairs foyer at a Christmas drinks do at the Royal Court theatre my first week in London. He had had a play running there – he was pointed out. I remember not liking the look of him much but I can’t remember why. It’s maybe because he was in the company of Max Stafford-Clark, the director of his play and Royal Court boss, with whom I had not hit it off: I had been appointed Young Writers’ Tutor in Max’s absence. Max objected to that. My predecessor in the job had been the great Caryl Churchill, but I don’t think it his objection had anything to do with me in particular – I was up and coming - but the fact that he’d not been consulted. (I’m pleased to say I held the job for four years, and was asked to stay on even then.) Hanif would take over from me. We crossed paths at that earlier time, too. Danny Boyle was a young director at the Court, who’d chosen, as his first production there, what I still describe as a ‘Polish Pantomime’ to direct. Danny had liked a stage play of mine and asked me to write a version of the Polish play, a subversive piece. We would travel to Poland which was still Communist, talk to the original cast and director, in a hush hush way. But I had a – very - good job in the offing at the BBC and couldn’t make much of the Polish play’s surreality. I turned it down (‘Good career move,’ someone said, later, when Danny was a film director). Danny had come up to Oxford where I was then living – the persuasive operator in him at work even then – to get me to change my mind. But I was adamant. Hanif took on the job. I remember Danny being surprised I drove a MG Midget, as I took him back to Oxford station. From my stage work he’d seen me as a gritty Northerner.

And then, 1982, there was Hanif on his own at Sheila’s party, handsome, funny. We got on, delighted in each other’s company, exchanged phone numbers etc. Hanif’s habit was to ring, generally late evening, and without introducing himself, would say something like, ‘I piss on your grandmother’s vulva.’ There may have been a reason for this approach that had to do with Arab curses, but I’ve forgotten.

Hanif was the kind of guy you had come to London to meet. He once said to me that not a single day of his life had gone by without someone referring to his race: he is, in fact, the son of a Pakistani father and an English mother. I met his dad once at the Hampstead Theatre where Hanif had a play, ‘Birds of a Feather’ and the old guy, who was a would-be writer himself, was thrilled for his son. Picked out – isolated - at school and elsewhere Hanif may have been, but his colour and background was the making of him as a writer (as well a certain ability, of course). Salman Rushdie had just had an enormous success with ‘Midnight’s Children’. The door was off its hinges and battered in for what at one time were called Commonwealth Writers. I was writing a lot of film for television then, and came across Hanif one summer or autumn evening – we were cycling on the towpath between Putney and Hammersmith. Hanif had seen one of my films the night before, an adaptation for Granada called ‘Miss A and Miss M.’ ‘I want to write films like that,’ he said. And had, it turned out, the vision to write films better than that. He had been commissioned by Channel 4 to write about young Asians in England, the film that became ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’, knew he was on a winner, thought it was more than a television piece, wanted a different director, stuck the script through Stephen Frears’ door, and an Oscar nomination was the eventual result. He had done all this without taking the advice of Sheila, our agent, who had urged caution (Hanif never really forgave her). I would never have had that assurance. We once had a meal - Hanif, Sheila and I – Hanif wanted me to be there because their relationship was still edgy, and he burst out at one point, his remark aimed directly at me: ‘You’ll never be very successful because you’re too nice.’ Extraordinary: it must have emerged from something I said. I don’t think I’m that nice (my closest friend certainly doesn’t think so). But I am ambivalent about success and the remark probably says more about Hanif’s approach and attitudes than about mine. Sheila would ring me every now and again, after that meal (we took her out jointly: she was touched), knowing we were pals, to ask how he was; was frank that she didn’t know how to handle him - and I learnt my place in the pecking order of her clients. Later he left her and encouraged me to do so. But I was happy for many years with Sheila. She had brought me on as a young writer. What I knew, not brilliant like Hanif, was I needed her more than he did.

I would meet him from time to time at the Dove, on the towpath near Hammersmith Bridge – he lived in Baron’s Court, me in Chiswick. Our bikes would be parked together on the railings: his more stylish than mine. They were the happiest times. Though I had fed him and introduced him to people, including the Kinnocks (whom he was keen to meet – Neil was Labour Leader then) there was never any repricocity. ‘Oh, you ought to meet Michael Hastings,’ (say) never led to any meeting. But we were thick. It felt like a love affair. When he was asked to tutor for the Arvon Foundation, the organisation set up by Ted Hughes offering a week’s residential course for young or inexperienced writers, Hanif asked me to accompany him as tutor. I wouldn’t have been asked otherwise, though the director of the Arvon at Lumb Bank is now my current radio producer, David Hunter. It was a near disastrous week in glorious weather - May, I think. I drove up to Yorkshire with Hanif, who couldn’t drive then, as passenger, he telling me to keep my hands on the steering as I pointed out places in South Yorkshire where I had taught. Of the fourteen or so students, about eight were from a black women’s collective in South London, attracted by Hanif as tutor. They all knew one another - too well, They were dour, which puts it cheerfully. There were disputes. They all seemed to be writing about Sickle Cell Anaemia. I was the diplomat in a way that, even less nice these days than then, I wouldn’t be now: this group was bitter and irreconcilable. There was some god almighty rumpus on the last night and we tutors left them to it on the basis of who were we to prevent them having a good scrap? The two of us (I’d say young-ish white males - though Hanif doesn’t qualify for one of the adjectives, and which perhaps proves his remark about ‘Not a day goes by…’) had a great time away from the fractious group, including at one point a visit to Sylvia Plath’s – defaced – grave among an overgrown graveyard. Later we had a card from David Hunter and his partner Moura, the organisers, commiserating and resolving never to allow an already existing group in such numbers as students. We went again a year or two later to tutor a much more tractable – and talented – group, and glimpsed Ted Hughes – who slipped in and out at the end of the bar/dining room, like a shadow.

Hanif had had his huge success with ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’ by then. I was doing pretty well in television and didn’t envy him: I regarded him as the ‘better’ writer, more confident and daring than me. This led to disasters, of course. His second film with Frears, ‘Sammie and Rosie get Laid,’ originally called ‘The Fuck,’ was charmless. He had asked me to bring Kinnock along to the preview, and just before the (split screen) ‘dirty bits’ Hanif nudged me in anticipation. Multiple copulations followed and on my other side Kinnock (who was with Glenys) whispered ‘We’re not used to this.’ The post screening dinner was glum. I had a chat with Frears who said, ‘I’d no idea what I was doing through most of it or what it was about.’ Sheila (with her husband) looked like thunder, though her marriage had turned rocky (‘Imagine an evening at their house’, Hanif said) and Salman Rushdie (pre-Fatwah) turned up.

Hanif’s own love life was complicated. When I brought him back down from Yorkshire after our second Arvon stint he said to me as we hit West London, ‘I want to come home with you.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, she’s there.’ ‘She’ being the woman he would soon marry. He had encountered many problems with his family over the world he portrayed in ‘My Beautiful Laundrette’ and was feeling isolated: ‘You have great friends. Mine are deadbeats.’ He was probably doing too many drugs, and, I remember, wanted us to spend a weekend on LSD together, wandering round Chiswick House and grounds or somesuch. But ‘the Nervous Nelly,’ as he called me, balked at that. I realised that I was performing the role of elder – wiser, more stable – brother, and wasn’t entirely comfortable with what we might now call the Jamie Murray role. One Saturday night he asked me round to his place. He sounded low and I bubbled away for about three quarters of an hour in his company before he told me his dad had died that week. He had put me in a false position. I couldn’t say it at the time because he was grieving but was quietly angry with him for not making his misery clear from the start. It was bizarre behaviour: I thought he simply needed cheering out of a ‘mood’. Later, writing a fine book about his father, he excluded me from the narrative, saying that the aftermath of his father’s death had been spent in isolation. It wasn’t. I was edited out.

But after years of ‘success’ things were not going so well for me. He wrote, or completed, his first novel ‘The Buddha of Suburbia’ and sent it me the manuscript up North where I was then staying. I didn’t like it much – found it cartoony, two dimensional – and wrote to tell him so. I said I thought he had missed a big opportunity to write the greatest novel about the theatre since ‘Nicholas Nickelby,’ completely failing to notice that ‘Buddha’ was ground breaking in its portrayal of British Asians. It made a good television series, but I think by then I felt that Hanif was having too much success on my territory, television (i.e. I was wasn’t). The worm had entered the bud.

He wanted me to dramatise a political short story of his, but I found the language of the story – ‘olympian’ or ‘neutral’ (like a translation ) and its premise unlikely - and told him so. My justification for this is he was savage with others’ writing. So an offer became a hurt. We were due to write a sketch together at a Royal Court fund raiser, but he was very late for our meeting and I went a bike ride by the river instead. He was critical of Kinnock during this period leading up to the 1992 General Election. It was easy to be so, but he went to print in the ‘New Statesman’ with a lead article about Neil’s failings. I had introduced them; Hanif had become one of his celebrity supporters. Kinnock phoned me: ‘You tell your friend, Hanif Kureishi, that (expletive deleted) rat etc.’ And mistakenly I did. I did, at least, wait till Hanif rang me. And tore him off a strip – what was the point of an article like that a couple of months short of an election? He was first silent, then evasive, and – I realised later – lied a bit. I’m not bothered (after near twenty five years) about the details of the row, but it was the end of the friendship. The Headmaster, so to speak, had got the Head Boy to do his dirty work for him and the (too obedient) Head Boy should never have complied.

I went a long wander in the Nineties, disillusioned with myself and my work. I know Hanif asked after me and I congratulated him on his answer machine when his twins were born. There was no reply to that – he didn’t take the (intended) opportunity to make up. His marriage later foundered, and Hanif wrote a brilliantly cruel novel ‘Intimacy’ about that break up. It verges but just avoids on the self pitying, and will outlast him. I wrote a postcard to him about that. No reply. His work subsequently has been patchy – but he allows himself the freedom to fail – and I find the films lack urgency, but I e-mailed him a couple of years ago to congratulate him on his CBE, and got a pleasant reply. There have been one or two more splutters of communication, including one on speculation about Stephen Kinnock’s sexuality (‘Are you responsible for this?’). I miss his humour – which isn’t on much display any more in his public pronouncements where - always with a slightly whiny voice - he appears lofty, even grandiose. That wasn’t his manner in those brilliant years of the Eighties, when I was nearly famous and he became famous - and I’m glad to have known him then.